Ecuador

Ecuador's Yasuní National Park, a global treasure and UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, became the epicenter of a fierce battle for environmental justice and Indigenous rights, culminating in a groundbreaking 2023 national referendum. A new mini-documentary by Democracy International captures the relentless fight of YASunidos and the people of Ecuador to preserve this fragile ecosystem, offering a poignant glimpse into how direct democracy can shape a sustainable future for all.

A decade-long battle to protect Ecuador's Yasuní National Park culminated in a historic 2023 referendum where nearly 60% of Ecuador's Yasuní National Park, a global treasure and a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, became the epicenter of a fierce battle for environmental justice and Indigenous rights.

A new mini-documentary by Democracy International captures the relentless fight of YASunidos and the people of Ecuador to preserve this fragile ecosystem, offering a poignant glimpse into how direct democracy can shape a sustainable future. The voters demanded the indefinite preservation of its natural diversity from oil extraction. Spearheaded by the YASunidos movement, this has been a tireless fight for Indigenous rights, environmental justice, and democratic integrity, showcasing a nation's refusal to sacrifice its natural heritage for exploitation. While the binding vote marked a critical victory through direct democracy, the struggle continues as Ecuadorians unite to ensure Yasuní's future remains safeguarded against ongoing threats. This is a story of resilience, hope, and the enduring power of collective action.

Natural heritage or natural resource?

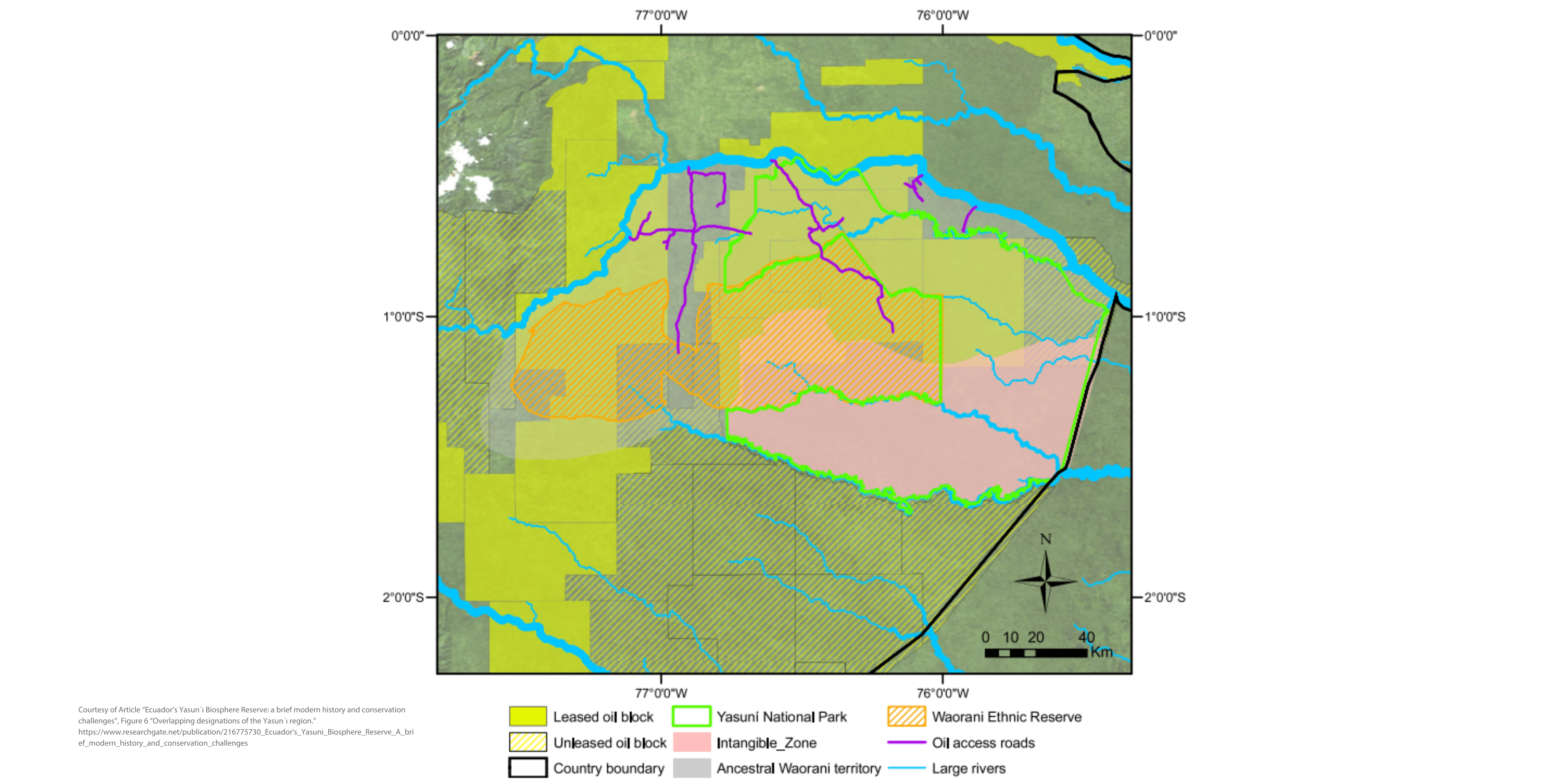

According to a study, the Ecuadorian Yasuní Biosphere Reserve, created in November 1979, is a place of great biological and cultural diversity. Located at the confluence of the Amazon, the Andes, and the equator, it boasts one of the highest concentrations of plant, amphibian, bird, and mammal species on Earth, making it a global biodiversity hub. It is also the habitat of two Indigenous cultures living in voluntary isolation – the Tagaeri and Taromenane, both belonging to the Waorani ethnicity. Local ethnic groups are historically characterised as strong advocates of their ancestral territory. Beyond its ecological and cultural relevance, the reserve also harbours a vast array of natural resources, including timber and substantial crude oil reserves, creating a challenging balance between conservation efforts and resource utilisation.

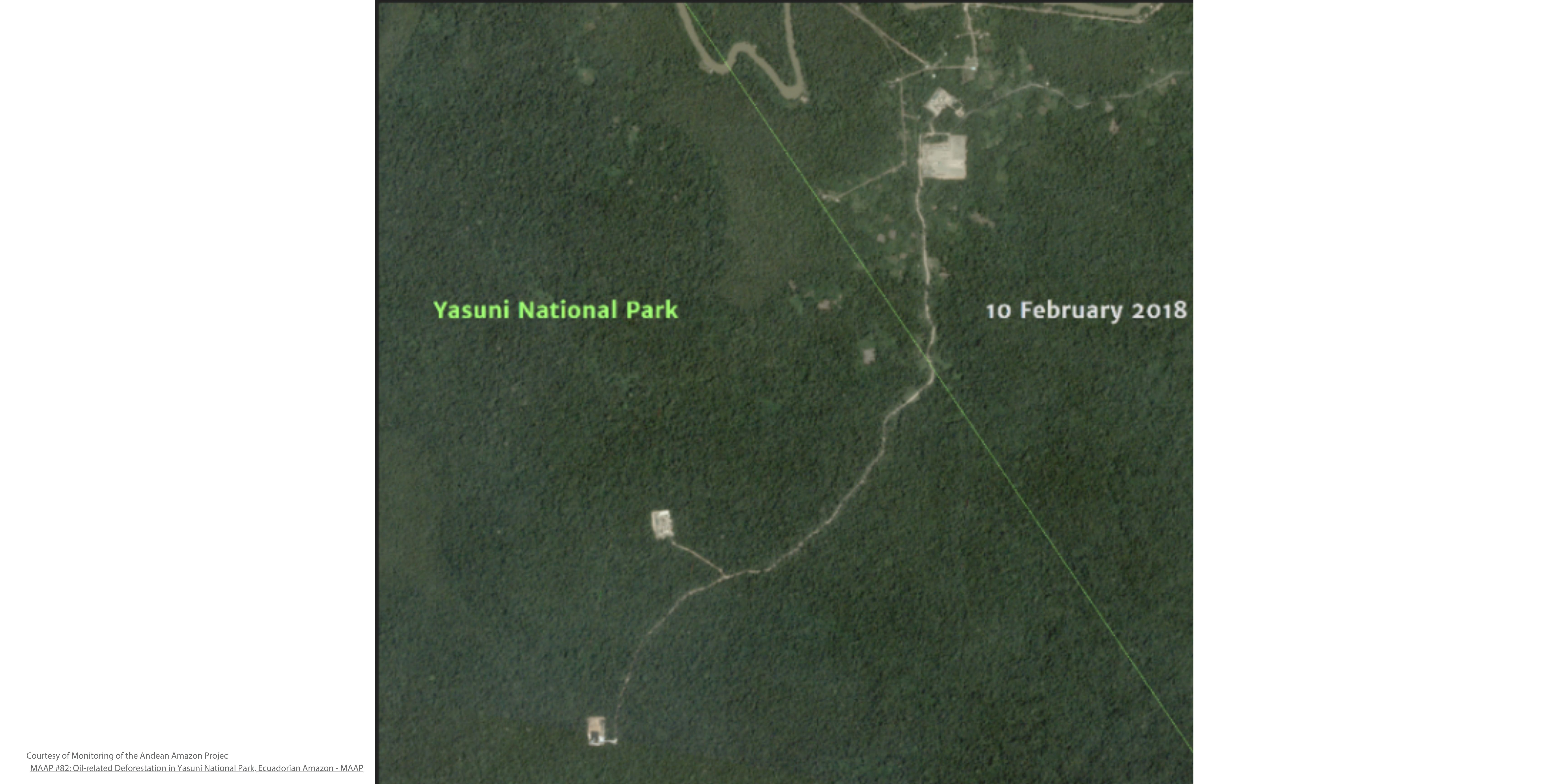

As an explanation to the readers, Yasuní National Park is one of the world’s most biodiverse sites. It is about four times the size of Luxembourg and covers 9,823 square kilometres. Block 43, the so-called ITT oil block (Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini), lies deep within this vast region and is 40% the size of Luxembourg. As of 2022, Block 43 had exhausted around 300 ha of forest – meanwhile, from January to June 2024, 50,454 barrels of oil per day were produced. The park and the block together highlight the immense scale and ecological importance of this unique location.

The Trust Fund idea: International Community Compensation

In 2007, through the, Yasuni-ITT Initiative, former president Rafael Correa made the significant decision to leave the country's second-largest untapped oil reserves in the ITT oilfields untouched. The aim of the initiative was to preserve the biodiversity of Yasuní National Park, protect indigenous populations living in voluntary isolation, and reduce CO2 emissions. In exchange, Ecuador requested $3.6 billion in international compensation over a period of ten years. This funding would allow the country to meet its financial needs without resorting to environmentally unsustainable practices. Ecuador's proposal, which sought to balance the competing demands of development and conservation, was an ambitious attempt to reconcile these interests. It has sparked global debate on how to finance the preservation of natural resources versus the extraction of those resources for economic gain.

In 2008, Ecuador became the first nation to give constitutional recognition to the inherent rights of nature. Chapter seven of the constitution marks a departure from classical environmental legislation, which typically views nature as either a thing or a commodity to be exploited for human purposes. In contrast, Ecuador's Constitution recognises Pacha Mama (Mother Earth) as a living entity with the legal right to survive, remain healthy, and perpetuate its life cycle, structures, and natural processes. At the heart of this shift is Article 71, which grants nature the right to "integral respect for its existence" and empowers individuals, communities, and public authorities to enforce these rights. Unlike traditional environmental regulations, which focus on human activity, Ecuador's system elevates nature as the rights-holder, establishing processes for communities to become protectors and defenders of ecosystems. Furthermore, the state is obliged to promote respect for all components of an ecosystem and issue restrictions on practices to citizens, companies, and communities that could threaten species with extinction.

In support of this initiative, the Yasuní ITT Trust Fund was established on 3rd August 2010 by the government of Ecuador, in collaboration with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The primary aim of the Fund was to secure international financial support for the protection of Yasuní National Park. Therefore, this initiative was designed not only to preserve the park’s unique ecosystems but also to foster sustainable development, including sustaining the way of life and traditions of Indigenous communities living in voluntary isolation, and ensuring a net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

The Trust Fund sought financial contributions from governments, foundations, and the private sector, with the goal of supporting Ecuador’s transition from an economy reliant on oil production to one based on sustainability.

Failing contributions

Whereas the Trust Fund can serve as a symbol of innovative global environmental and financial partnerships to protect natural areas such as Yasuní, the Ecuadorian Fund never really took off. Fundraising efforts met with considerable difficulties, such as slow contributions from the international community and eventually increasing skepticism towards the feasibility of the effort.

In a dramatic turn of events, the project came to a screeching halt in 2013 when the Ecuadorian government formally terminated the Yasuni-ITT Initiative. Instead of the aimed-for $3.5 billion, only a paltry $13 million from donations and $116 million from pledges had been collected over six years' time—a far cry from the goal. In the face of economic problems and lack of assistance, Correa announced that Ecuador would now start oil drilling in the Yasuni region to finance development.

Time for grassroots action

After the decision was made to extract oil from Yasuní National Park through top-down government policies, Ecuadorian citizens, particularly indigenous communities living in and around the park, decided it was time to take action.

This marked the launch of a formal citizens initiative later known as the "Yasuní-Referendum" which became a turning point.

A citizens' initiative that triggers a referendum is a democratic tool allowing citizens to directly vote on important matters. By collecting signatures, they can call for a binding national vote in Ecuador, where the public has the power to approve or reject specific issues, ensuring that government actions align with the will of the majority.

To trigger the referendum, a collective was formed, known as YASunidos. This group of citizens started the initiative and later campaigned before the referendum vote. However, the collective—representing environmentalists, indigenous peoples, and civil society activists—first needed to collect more than 500,000 valid signatures.

Activities to collect signatures in favour of the referendum were carried out for many years because of the social rejection towards the oil exploration in the Yasuní region - in favour of economic interests. However, the YASunidos successfully gathered the required signatures and presented over 736,000 signatories to the Ecuadorian Electoral College.

At this stage, the Electoral Council was tasked with verifying the validity of the signatures. However, the process was marred by widespread attempts to discredit the signatures, with accusations that some were repetitive or fraudulent. As a result, the Electoral Council ultimately refused to validate the initiative, which led to the referendum being blocked from going ahead.

As a result, from 2014 onwards, the Yasuní-ITT Initiative was effectively cancelled, and oil extraction in the park resumed. One might have expected the momentum of the citizens who collected 736,000 signatures to fade, but quite the opposite happened. A long legal battle began to verify the validity of the signatures. Throughout this process, many supporters remained committed, including the Yasuni-ITT tribunal, which played a key role in advocating for the cause.

The legal route - fighting for a referendum

In January 2014, the International Rights of Nature Tribunal decided that the plan to exploit oil in Yasuní might violate the rights of nature. The Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN), an environmental law group, set up the Yasuni-ITT tribunal in response to the Ecuadorian government’s decision to cancel the previous Yasuni-ITT Initiative.

The tribunal was not a court case, but more of a suggestion or advisory process. Its goal was to hold Ecuador accountable for the harm caused to the environment and human rights by oil extraction in Yasuní National Park. The tribunal wanted to understand how this decision affected nature’s rights, indigenous communities, and the international concern about protecting the environment.

The tribunal pointed out that the Ecuadorian Electoral Commission violated the right of Ecuadorians to political participation when it wrongly cancelled hundreds of thousands of signatures in citizens' initiative. Finally, the National Electoral Commission committed a violation of Ecuadorians' right to political participation.

This legal route took almost ten years, from 2014 to 2023. During this period, the continuous oil exploration in Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park led to a series of significant protests, mostly from environmental campaigners and indigenous population.

Direct democracy enables citizens to participate directly in the decision-making process, allowing them a voice in issues that concern their day-to-day life and future. This is precisely what Ecuadorians did. They used a referendum to assert their will and protect the Yasuní region from oil exploitation, highlighting the critical role of citizens in shaping the country's environmental and social policies. The referendum called in Ecuador was authorised through Article 104 of the Constitution, which grants citizens the right to initiate referendums who manage to collect the necessary number of signatures from issues that affect the country’s fundamental interests. It is a mechanism designed to allow direct participation in national decision-making.

The constitutional court

On 9 May 2023 the YASunídos presented their case in the Constitutional Court, and the national referendum was approved with the following question: ‘Do you agree that the Ecuadorian government should leave the crude oil (in Yasuní National Park, also known as Block 43) in the ground indefinitely?’

Now, the YASunidos and everyone advocating for leaving the oil underground in the Yasuní National Park faced an even greater challenge: convincing the public to vote 'Yes' on the referendum question to protect the park.

They crafted a multi-faceted campaign strategy that included protests, artistic expressions, and a wide array of creative methods to raise awareness. Through murals, performances, and music, they brought the message of the importance of nature, indigenous cultures, and biodiversity to life. These efforts, along with the support of countless volunteers from local communities, helped amplify the movement far beyond the borders of the park itself, reaching people in urban areas, big cities and especially regions distant from the park itself.

The campaign sought to inspire people to recognise that preserving the natural beauty and cultural heritage of Yasuní was far more valuable than short-term economic security. It was a call to protect something far greater—an irreplaceable part of the planet’s ecosystem.

Election day

On 20. August 2023, a resounding majority of Ecuadorians voted on a ballot against specifically the extraction of oil from block 43 of the Yasuni park. Nearly 60% (58.95%) of the more than 82% of people who turned out to vote said 'Yes' when asked if they supported the Ecuadorian government's decision to keep the ITT crude, known as block 43, underground indefinitely.The rejection of oil exploitation in the Yasuní park by Ecuadorians is an illustration of the crucial role of direct democracy as a means of the national policy decision-making process.

The Yasuní-Referendum shows that direct democracy can be a powerful bottom-up instrument for resolving situations, in which the public interest and the action of the government may be at odds. Besides its effects at the national level, the referendum outcome has set a global reference point on the use of direct democracy in facing climate issues. Accordingly, this decision represents a turning point in terms of how countries should manage climate related issues and represents the growing weight of inclusion into policy development - in this specific context, citizens and, more particularly, indigenous populations.

The battle continues

However, over more than one year after Ecuador's historic referendum to protect the 43-ITT oil block in Yasuní, the government has not fulfilled its responsibilities, no concrete plan, budget or schedule for dismantling infrastructure has been put in place. Further, although a government committee was set up in May 2024, it did not include Indigenous representation and subsequently was rejected by the Waorani, Kichwa, Tagaeri and Taromenane communities, who called to be included directly in the process.

Although there has been a community decision, what we are witnessing now is a serious concern about the future of Ecuador's democracy. Failure to respect the people's vote could have grave consequences and create a negative precedent for future events. As for the choice of the people not being respected, what will the repercussions be? In addition to undermining Ecuador's democratic process, disregarding the people's decision also erodes confidence in the government's capacity to keep its commitments. It will, at the very least, affect the voters in the same way the next time one attempts to challenge the system and policies to this extent.

Watch the full story told by the YASunidos themselves.