Never before have so many people around the globe taken part in popular votes as in 2019. Yet never before have representative governments worldwide come under such pressure from street protests. What does this mean for democracy in 2020?

It all started underground, in Santiago de Chile’s 140 kilometre-long, 136-station metro system.

Inaugurated by military dictator Augusto Pinochet in 1975, the subway in the Chilean capital represents both the best and the worst of one of South America’s richest countries. While a symbol of impressive economic development, it’s also a reminder of the undemocratic roots of the political system, whose constitution was adopted in an unfree plebiscite on September 11, 1980.

It’s also a sign of the city’s social divisions, says Paola Jirón, the director of MOVYT, a Chilean inter-university mobility research centre: the 7 million-strong capital is a highly segregated place, and millions of mostly poor people commute each day to for work, often to richer parts. On the long, overcrowded commutes they share problems and discuss solutions.

“In the Metro we have experienced the huge inequalities of our society for a very long time”, she says.

So, when the operator, Empresa de Transporte de Pasajeros Metro S.A., announced this summer it was raising the price of single-trip tickets by 30 pesos – about 5 U.S. cents – it unleashed a flood of discontent. As a protest against this latest in a long series of price-hikes, students began jumping the turnstiles, and what followed morphed into the biggest demonstrations the country has seen since the end of dictatorship thirty years ago.

And as during the years of Pinochet, the police and military reacted harshly – killing dozens, hurting hundreds and arresting thousands. It took millions of peaceful protesters taking to the streets to change this, and in mid-November, Chilean president Sebastián Piñera announced a direct democratic process to draft a new constitution for the country.

“In the past four weeks, Chile has changed”, he said, promising “no impunity” for security officers who had violated protestors’ human rights.

Together with civil society organizations, the main political groups in parliament have thus agreed to democratize the country from the ground up: on April 26 next, the people will decide if they want a new constitution. If they do, they will then also decide if they want it to be drafted by a fully directly-elected “Constitutional Convention” or a “Mixed Constitutional Convention” (half-composed of sitting members of Parliament, the other half directly-elected citizens).

Next steps will include an election to determine the makeup of this Convention and finally – in 2021 – a confirmatory vote on the result. Efforts are also underway to secure the proper representation of all social groups in this future convention, including women and indigenous people, says David Altman, a Uruguayan politics professor teaching in Santiago.

2019 – similarities with 1989

As remarkable as this Chilean story is, it’s also typical for a year in which more people have taken part in both protests and elections than ever before.

On one hand, the biggest electoral processes in history took place in the first half of the year in mega-polities like India, the European Union and Indonesia.

At the same time, representative governments in countries from Algeria to Lebanon and Britain to France came under severe pressure from popular protests. Even Switzerland wasn’t immune, although here, many protests were less about fundamental national policies – in this respect the Swiss have plenty of opportunities to express themselves at the ballot box each year – than about international issues like Tibet, or local issues like housing.

In a year when the anniversary of the Berlin Wall collapse was celebrated, it’s worth noting that the situation today has many similarities with the one 30 years ago: we see comprehensive popular challenges to representative (elected) governments, which in the eyes of many people – especially young and female – are not as representative as they should be.

“We can identify efforts worldwide to make democracy more democratic”, said Kevin Casas-Zamora, Secretary General of IDEA, when presenting the institute’s 2019 “Global State of Democracy” report in Mexico in December.

In the report, which evaluates hundreds of democratic criteria compiled by the Varieties of democracy-project, IDEA offers an empirical insight into the persistent spread of democracy worldwide, but also its inherent challenges – such as a lack of response to citizen’s needs, populism, and fake-news.

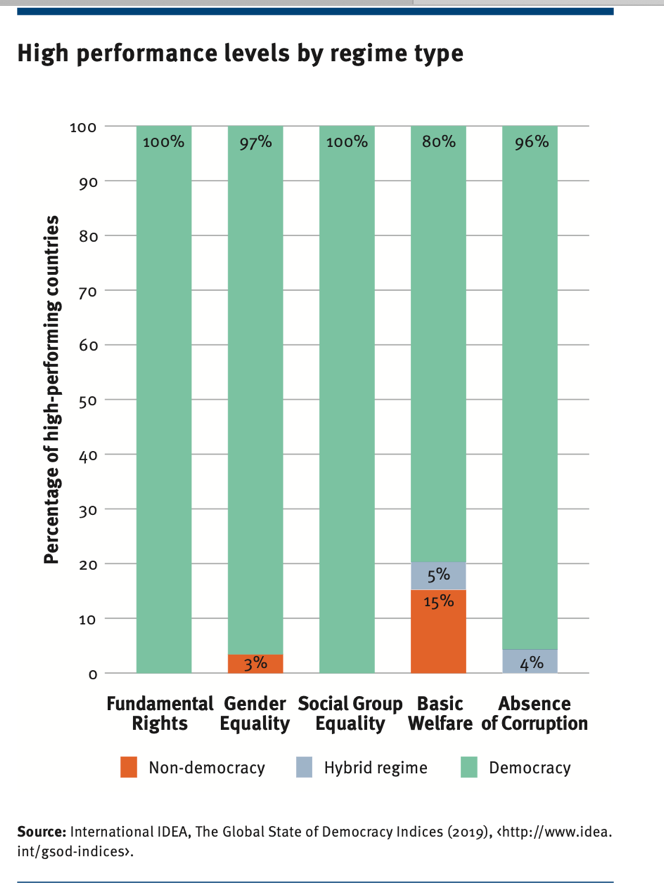

One of the most intriguing findings is the relationship between stronger democracies and the quality of governance when it comes to key issues like human rights, gender equality and basic welfare: “More democracy means better and more equal societies”, states the report.

The findings also play into possibly the most global of all issues: the climate challenge.

Here, on the one hand, individual governments as well as the international community are having a hard time agreeing on necessary steps to cap emissions. At the same time, new research by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and civic movements like #Fridaysforfuture are pressing for immediate action.

It’s a tension that needs tools, and 2019 might have given some indications: for example, we saw the strengthening of the European Citizens’ Initiative (which allows one million EU citizens to collect signatures to put legislation on the agenda of the European Commission), as well as the new World Citizens’ Initiative, directed towards the UN General Assembly.

Similarly, 40 big city governments from around the world have taken the lead for a more sustainable future by acting together on the local level – showing that, beyond national negotiations, direct routes to action exist.

What does this mean for democracy in 2020?

Next year, we’re likely to see the continuation of this fundamental shift from limited representative government to more fully-fledged representative democracies, featuring comprehensive participatory and direct democratic rights.

But while significant – or almost revolutionary – change can happen within weeks like in Chile, most often it takes years to transform street protests into institutionalised modern democratic institutions. And, as we saw in 2019, even free and fair elections may not be enough to overcome gaps between institutions and citizens: in countries like Israel, Bolivia, Algeria or Spain, repeated elections have not yet offered significant ways forward.

Electoral decisions around the world will nevertheless offer major milestones in 2020, with votes happening in Taiwan (January 11), Israel (March 2), South Korea (April 15) and the United States (November 3). The latter will feature not only a highly polarized presidential vote, but also many other key decisions including initiative and referendum votes in 26 out of 50 states.

Other key regions to watch are Hong Kong (after the ballot success of the pro-democrats in November 2019 elections), Catalonia (where most people are still waiting for a proper dialogue with the central powers in Madrid) and Ethiopia, where the first free and fair elections in decades could take place under the leadership of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the winner of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize.

As in 2019, expect more ballots, and more protests.

Image credit: (Associated Press - courtesy of Swissinfo)