A digital version of the Deliberative Poll encourages democracy, more cheaply.

This column was originally published by Zócalo Public Square. Photo credit: via Flickr by Josh Heller, Creative Commons license 2.0

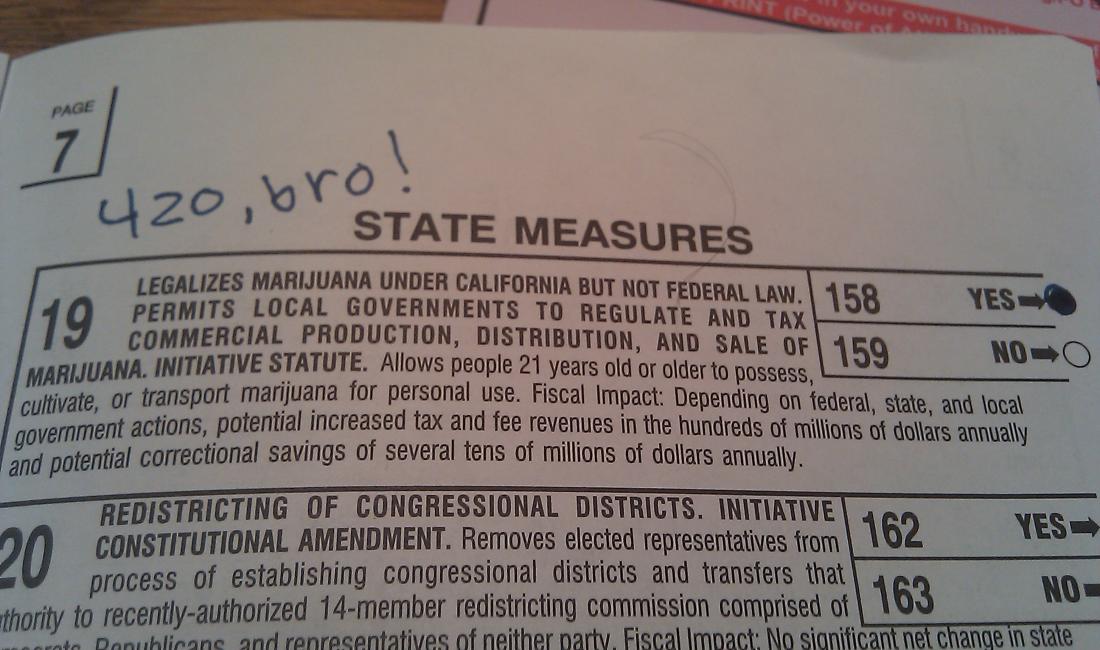

Californians vote on many ballot measures, but we almost never participate in significant public debates and discussions about the measures’ contents and impacts.

This isn’t simply a result of apathy or poor civic education. Rather, it’s an example of “rational ignorance,” a term coined by the late Stanford-educated economist Anthony Downs in his 1957 book, An Economic Theory of Democracy. The term defines this democratic reality: since you have just one vote out of millions, your individual vote doesn’t really matter. So, it’s rational to remain ignorant about the details of measures on the ballot.

In California, this means that we have little reason to devote our precious time to acquiring information or coming to a considered judgment about all the complex measures on our ballots. The problem is that when too many of us remain rationally ignorant, our election results may not match our preferences or the public interest.

This year, however, political and computer scientists at Stanford, in collaboration with think tanks and civic groups, are seeking to counter our rational ignorance with an advanced tool: a digital Deliberative Poll.

The poll would give a random sample of hundreds of Californians the time and opportunity to do serious deliberation on certain ballot measures. The specific ballot measures to be used in the process have not been determined, but one set of likely candidates for deliberation are three competing constitutional amendments involving the voting requirements for taxes. One of the amendments was proposed by business and anti-tax groups, one by the legislature, and the last by local governments.

The amendments are the kind of complicated measures that can confuse voters and encourage our rational ignorance, even when they have real effects on our communities and pocketbooks.

Here’s how digital Deliberative Polls work. Stanford’s Deliberative Democracy Lab assembles a representative sample of the California electorate. Participants are paid for their time (which is expected to be about a day and a half) and reimbursed for any child- or elder-care obligations. Their internet speeds are increased, if necessary.

First, the platform, which was developed in collaboration with Stanford’s Crowdsourced Democracy Team, polls participants on the ballot measures to establish a baseline. Then, some members of the group deliberate. (The rest are in a control group that doesn’t participate at all in the deliberation, to help measure the impact of the deliberation on results.) The platform is AI-assisted—there is no human operator—and it speaks in English in the voice of Alice Siu, associate director of Stanford’s Deliberative Democracy Lab.

Next, the platform randomly divides the sample into small groups of 10 to engage in video-based dialogue to consider the pros and cons of the ballot measures and decide on key questions to ask panels of experts representing different points of view. The participants ask their questions in plenary sessions by video. The small group deliberations and the sessions with all the groups present alternate throughout the process.

The AI tries to facilitate a discussion that is equal. Speakers are limited to 45 seconds at a time, and the tool nudges reluctant participants to speak up. The platform can also intervene if people become uncivil.

At the end of the deliberations, participants (and the control group) are polled again on the measures. The difference between the before and after survey results are shared with the public, to demonstrate the impact of deliberation on views of the measures.

“It is a social science experiment and a form of public education,” said Stanford’s James Fishkin, who leads the polls and the Deliberative Democracy Lab. “It overcomes ‘rational ignorance’ because each person, instead of one voice in millions, has one voice in a small group of 10 engaging in meaningful dialogue.”

Fishkin originated the concept of the Deliberative Poll as an in-person event, back in 1988, and has deployed it on issues ranging from Korean reunification to civil service reform in Brazil.

Recently, Fishkin and his team conducted a series of Deliberative Polls known as “America in One Room” that aimed to address partisan divides and deadlock by getting Americans of different views to deliberate with one another on topics ranging from energy to immigration to democratic reform. Those Deliberative Polls showed that such conversations can still produce common ground, even amid nationwide polarization.

Fishkin and Siu, both California voters, say that we badly need to combat rational ignorance in our ballot proposition system through deliberation. Some get little or no public notice. Campaign donations from special interests determine which measures get on the ballot and often, which win. Measures have grown increasingly long and complex, defying voters’ attempts to understand them.

The momentum to use Deliberative Polling in California dates back to the attempted 2021 recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom, which increased public concern about flaws in California’s direct democracy.

In response, Secretary of State Shirley Weber asked the bipartisan team of former Gov. Jerry Brown and former Chief Justice Ronald George to make recommendations for reform of initiative, referendum, and recall. They were assisted by Nathan Gardels of the nonpartisan Think Long Committee for California and the Berggruen Institute.

The Think Long report lamented the absence of a public, institutional platform for informed deliberation on ballot measures. A 2022 Public Policy Institute of California survey also found 77 percent support among likely voters for an independent citizens commission to study ballot initiatives and make recommendations to the public.

Today, Think Long, Berggruen, the Stanford team, and civic groups are circulating a proposal to funders to apply Deliberative Polling to the three competing taxation measures that could be headed to this November’s ballot. (Full disclosure: I’m a fellow in Berggruen’s Renovating Democracy program this year, and have participated in discussions of the Deliberative Poll.)

Fishkin and Siu say Deliberate Polling can be especially effective when multiple measures address similar issues—as with the competing taxation amendments. They recently held a well-received Deliberative Poll around four different proposals to the Finnish parliament (which showed that the AI platform produced similar results to deliberations with human moderators).

Fishkin said that campaigns and stakeholder groups on opposing sides of measures participate in the deliberations because they want to have their best case heard. Research shows that participants stand to gain because being part of processes like a Deliberative Poll makes them more engaged and better informed.

The rest of us can become less ignorant about ballot measures by seeing the deliberations and their conclusions, which will be publicly reported.