Democracy International’s intern Darragh Power gives in inside on the TRANSEUROPA Assembly in Palermo that took place in October 2021. Traveling to Sicily, he attended the assembly as a participant. His experiences, impressions and thoughts on the event build the basis of this report.

While the Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFoE) held its second plenary meeting in Strasbourg, another complementary assembly took place in the periphery of Europe, at Palermo, Sicily. The TRANSEUROPA Assembly in Palermo marked the culmination of a series of similar events – “Assemblies of Solidarity” – that were held in twenty locations across Europe, in ten countries, which also discussed the future of Europe. Some of these participants, myself included, finally came to meet in person under the old, roofless church of Lo Spasimo with local citizens from Palermo and Tunis, organizers from European Alternatives, in cooperation with the European Parliament, and other members of the Citizens Take Over Europe coalition. The question at the top of our weekend agenda: how to prevent environmental catastrophe?

This focus did not relieve my conscience from feeling somewhat guilty and hypocritical for flying to attend a conference on climate change. Nevertheless, I had vowed (to myself – and anyone that would hear me out) that my active participation and positive contributions at the Assembly may offset my CO2 travel costs, in the greater scheme of things. Which brings up the issue of personal versus systemic responsibility. Is taking a flight fundamentally worse than choosing plastic over paper bags at the shopping counter? Or is it only a difference of degree? And with whom does the responsibility for change lie – especially when those most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions are either unwilling to lead the change or dead?

Just as muscle is built during the rest period following an intense workout, I come to a greater understanding of the Palermo Assembly as I reflect on the events of that weekend. I look back and see a semi-structured collective experiment attempting to build a better boat in a storm. But I also see people lost at sea, struggling to hold onto plywood rafts. Our group deliberates, talks with experts, makes proposals and we collectively form the Palermo Climate Declaration.

Time for a Change

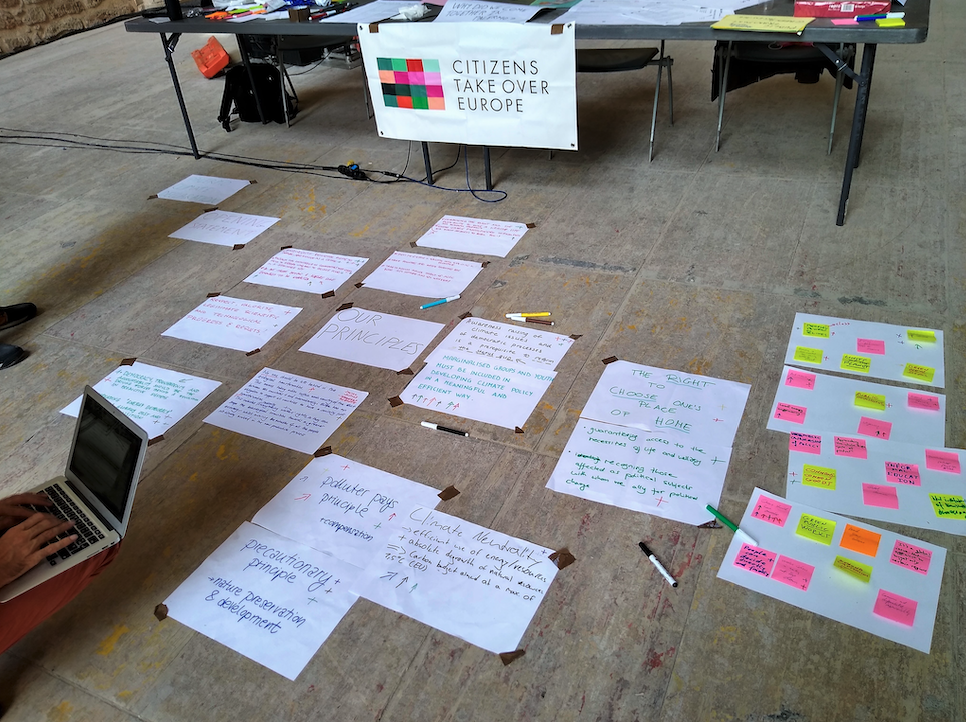

Kicking off the the event, principles highlighted by previous assemblies were gathered together under six loose streams, and we joined whichever one interested us most. Vincenzo, a local from Palermo, and I joined the group on climate refugees, facilitated by Kasia Wojcik. We began by discussing the inadequacies of the humanitarian framework, which tends to depoliticize people. We also questioned whether it actually made sense to distinguish between different types of refugees. Does it risk constructing “desirable” and “undesirable” refugees? Is crippling poverty, for instance, less valid a reason for leaving one’s home behind than environmental damage? Why do people feel compelled to leave their homelands behind in the first place? Shouldn’t the international community focus on preventing, mitigating and alleviating these underlying causes? We thus proposed that people should have a right to choose their place of home – to stay or to leave. We lay our principles on the ground and highlight those which we think matter most and should be worked into our climate declaration at the end of the day.

Following lunch, I had an illuminating conversation with one of the guest speakers, Erwin Mayer, who is a board member of Democracy International and spokesperson for Mehr Demokratie Austria. We talk about the ancient Greek Kleroterion – a device used to randomly select eligible Athenians to positions of power, which they would hold for a limited period of time under conditions of accountability. The idea was to avoid the corrupting influence of power. Citizen assemblies often rely on this random selection of participants, which potentially curtails the influence of special interest groups and career politicians. That is, according to Erwin, if certain other conditions are met – such as having initiatives emerge in a bottom-up manner from the people (e.g., after reaching a threshold of signatures within a given timeframe) that result in citizen deliberation and binding referenda.

At any rate, neither of us are talking about democracy as the commonplace idea of “one person, one vote”. We’re both disillusioned by representative democracy, subject as it is to corporate influence and careerism. But what about affected-led governance? Shouldn’t those people who are most affected by policies be directly involved in the formulation of those same policies? Erwin raises the challenging issue of how one differentiates between the many that may claim to be directly affected. He mentions an example from home, when he was confronted with NIMBY-ism (“Not in my back yard”) concerning the planned construction of a new bicycle lane. Should public administrators yield to the interests of the residents, or does the public benefit of improved bicycle lanes win out? Should a compromise solution be found? At any rate, it’s not always easy to determine which affected groups really matter most - perhaps that remains an ongoing political decision for progressives to identify and ally themselves with.

It’s time for some input from the experts before we break into working groups. As one of the guest speakers, Erwin outlines his model of direct-democracy infused governance. Next, Andrea Salimbeni, R&D engineer and activist with EUmans, speaks to us about energy. He talks about the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) and its inadequacies. Following both speakers’ presentations, we break into two working groups to focus on either democracy or energy – tasked with proposing policies in each area to reflect the principles we had earlier determined. I found the task challenging in the energy working group. We focused on proposals to incentivize sustainable behaviour and discourage conspicuous consumption. But our intervention seemed overdetermined by the imperative to respond to market logic. It made me think that such important decisions cannot be left in the hands of just a few privileged persons. If we’re to properly address climate change, in a just and effective manner, we need to involve people from all walks of life in decision-making processes.

That same weekend, a number of us attended an evening talk at the nearby Piazza Mediterraneo Pubblica, organized by residents of the makeshift migrants’ camp of Campobello. Their homes had literally burned to the ground a fortnight beforehand. A man died in the fire. They had no water at hand to put out the flames and could only look on as the fire consumed what little they had. “You thought we had nothing beforehand; now we really have nothing.” The most vulnerable and least responsible people on planet Earth for climate change are already those most negatively affected by its consequences.

When we think about effecting urgent change – not only ecologically, but also socially just – one of the main issues concerns the finitude of our existence. The promise of prosperity for all cannot reign supreme over perpetual practice of modern slavery. Capitalism has divided the world into two. Those who count and those who do not. It has been divorced from its liberal-democratic prototype and entered into a polyamorous relationship with all cultures, including authoritarian ones. As liberal democratic systems (themselves scarred by democratic deficits and years of austerity) struggle to compete with authoritarian variants of capitalism, we might ask ourselves, as Bob Dylan did in the 60’s, “how many years can some people exist, before they're allowed to be free?”

When I reflect on the origins of our modern economy – in colonialism, exploitation and extraction – it occurs to me that we have not left them behind. We still rely on fossil fuels to move and feed our cities. We still rely on exploitation, which is often outsourced; there is no Apple without Foxconn.

The Conference on the Future of Europe offers a chance for citizens to be more engaged in the decisions that affect their life, but it is not nearly enough. Parallel assemblies, such as the Palermo Assembly, offer citizens space to discuss these important issues – but again, not everyone’s at the table and nothing’s legally binding. Acutely missing at the decision-making table are those who will be most affected by climate change, despite being least responsible. Their voice matters. Until their voice attains a proper say in political and economic decisions, our discussions will ring hollow. Have you any other suggestions how to build caring, resilient, response-able communities?