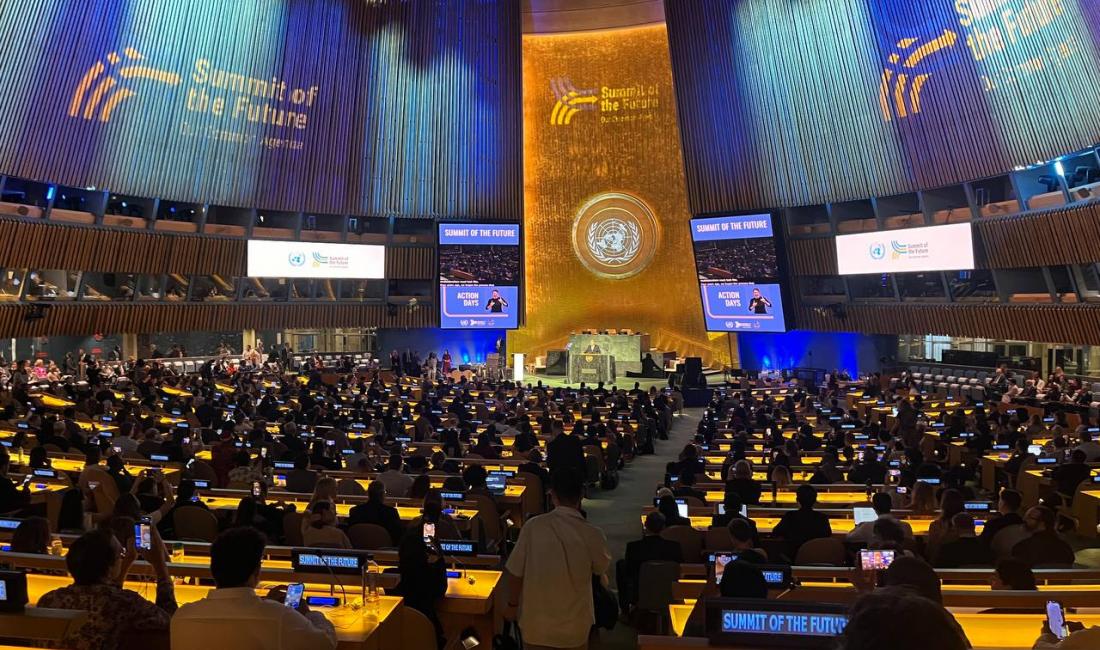

In New York, the Summit of the Future is wrapping up after two Action Days open to civil society and two Summit days with heads of state and government in attendance. On Sunday 22 September they adopted the Pact for the Future.

Immediately at the outset of the Summit, Member States adopted the Pact of the Future, which has been a long time in the making and had been hailed as a once-in-a-generation reset of the United Nations.

What is it?

The Pact of the Future is a global agreement, adopted by the member states of the United Nations by consensus acknowledging the challenges we face as humanity: climate change, AI, war and the need for an improved global governance system that addresses these challenges efficiently.

How did we get here?

Four years ago, at the 75th anniversary of the UN, a large stock-taking operation took place: 1,5 million people were consulted on how they see the UN and what they wanted for the UN in the future. It identified a crucial democratic deficit and a feeling of disenfranchisement when it comes to global governance while recognising the enormously important work the UN does.

This culminated in Secretary General Guterres’ Our Common Agenda report which set out priories for the future of the UN which included the axis „Updating the UN“ and called for more participatory mechanisms for citizens and better access for civil society. Calls we also address in our We the Peoples campaign.

The Summit was originally planned to take place in 2023 but was postponed, in part because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which of course altered the international context substantially. The pact has been drafted by the co-facilitators Germany and Namibia, based on inputs from member states and other stakeholders. A first draft was published and then negotiated with member states over several rounds. It was opened to civil society inputs through a civil society conference in Kenya in May.

The final draft was published on 13 September and put up to a vote yesterday. In a dramatic and unexpected move, Russia proposed a last-ditch amendment to strengthen language on non-interference in states‘ internal affairs and weakening language on women‘s rights. This cynical proposal was strongly condemned by the members of the African Union and Mexico and the amendment was side-lined and the Pact adopted.

What is in it?

The Pact of the Future crucially acknowledges the need for an improved global governance. It opens the door for reform of the Security Council, paving the way to expand its membership to address some historic inequalities and improve representation of African, Asian Pacific, Latin American and Caribbean states. It also specifies it wants to limit the scope and use of the veto. It includes the first commitment on nuclear disarmament in a decade. The Pact is accompanied by a Declaration on Future Generations and a Global Digital Compact which sets out principles for improved digital rights and signifies the first international agreement on artificial intelligence.

What is not in it?

It‘s almost a miracle that the Pact was adopted at all given the global context and the need for consensus. The downside of this is that language on contentious issues has been significantly watered down over subsequent rounds of negotiations.

Some of it is baked into the state-based nature of the United Nations: language on citizen participation, relatively prominent in the Our Common Agenda report and related consultations, did not even make it into the first draft of the Pact. Language on civil society representation was severely weakened, even striking out a mention of „new approaches for continuous and open communication“ and "ongoing. dialogue between formal meeting" with civil society that was included in older drafts. The Pact even specifically mentions it wants to preserve the intergovernmental character of the UN, signalling an unwillingness by member states to open up global governance to non-state actors. It does include commitments to work more closely with subnational and local authorities, something we can applaud given that they are more close to people’s daily lives.

The fact remains of course that only 40% of states are democracies, leaving their populations completely locked out of global decision-making and at the mercy of authoritarian regimes when it comes to addressing the global challenges that threaten their very lives and livelihoods. Unsurprisingly, authoritarian states blocked any language on democracy in the pact, leaving it up to civil society and democratic states to work with the provisions of the Pact and ensure stronger commitments to global democracy.