And the Role of AI, And What It Means for Local Democracy

This essay was produced and published by the National Civic Review. "Wires Crossed" image by Joe Mathews, using Google Gemini.

After a century of relative stability in our forms of government, we have entered an era of crisis and potentially dramatic change. The twentieth century model of representative democracy—built on periodic elections, professional bureaucracies, and citizen deference to expertise—can no longer contend with the systems of competitive authoritarianism that have emerged in the twenty-first century. Meanwhile, revolutionary new technologies could make the situation significantly better, or markedly worse.

These tectonic shifts are more fundamental than concerns about partisan polarization or complaints about government inefficiency. We face a fundamental mismatch between the democratic institutions we inherited and the capabilities, expectations, and technological realities of contemporary American society.

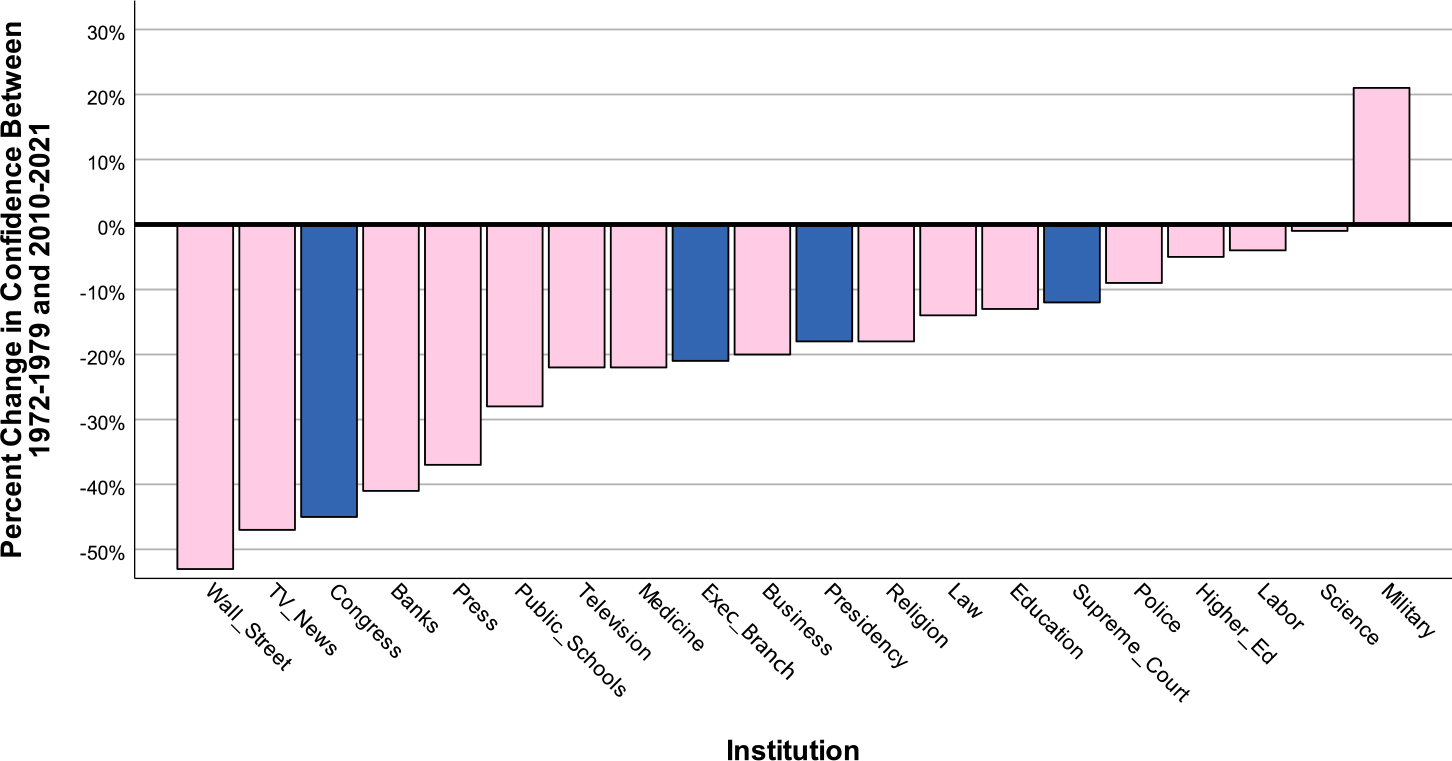

The result is a dangerous vacuum of trust and public confidence that threatens not only our current political system but also the very possibility of effective governance in an era when such cooperation has never been more essential.

While these shifts are affecting the country as a whole, it is at the local level where the state of public problem-solving is most evident and most open to improvement. This is where the rubber hits the road, literally: people are more aware of the pothole on their street than one in another community, and they are better able to take part in identifying, analyzing, and solving problems in their own neighborhoods than ones that are more distant. When local democracy doesn’t appear to work, people lose faith in the whole notion that we can make decisions and solve problems collectively. We are facing a national crisis, but it affects people locally, and it can be addressed locally.

Some of this identification, analysis, and implementation can now be enhanced through the use of artificial intelligence. But while generative AI can raise our capacity to solve problems, tapping that vast potential requires that we apply the lessons we have learned from both the Progressive Era of the past and the democratic governance of today. Without that learning and foresight, AI may become just another horrific tool for authoritarians to wield.

Does government deliver? (and how do we know?)

At every level of governance, there are many services to deliver and problems to solve. Wealthier residents want their roads paved, trash picked up, neighborhoods policed, and streets plowed. The most vulnerable people in our society have more pressing needs: food, shelter, and decent jobs. Those in between are concerned about childcare, transportation, education, and health care.

But while some failures in problem-solving, such as potholes and graffiti, may be obvious, the performance of our overall governmental problem-solving apparatus is not. The vast network of public goods and services that make modern life possible—from food safety inspections to weather forecasting, from basic research that enables technological innovation to the regulatory frameworks that prevent financial collapse—operates largely invisibly to most citizens. Even at the local level, millions of reasonable Americans across red, blue, and purple communities have little understanding of what their governments, school systems, nonprofits, or charitable organizations do. This invisibility creates a dangerous vulnerability: people rarely value or defend what they do not see or comprehend.

These attitudes are not, for the most part, based on a solid understanding of what governments do or whether public problem-solvers are ethical, capable, or committed. Even if governments dramatically improved their problem-solving capacity, most people probably wouldn’t know.

Democratic legitimacy depends not just on electoral consent but on the level of public understanding and trust. When citizens cannot connect their daily experiences to the work of public institutions, democracy becomes an abstract concept rather than a lived reality. The social contract that binds citizens to their government weakens, creating space for demagogues and authoritarians to exploit.

The transformation of American citizens

A common reaction to Americans’ lack of knowledge about government is simply to educate them. But this is more complicated than it may seem: because people are deluged with information on a daily basis, any single set of facts is less likely to penetrate and be absorbed. And describing the workings of government as if it were a well-oiled, smoothly functioning machine just arouses further skepticism among jaded citizens.

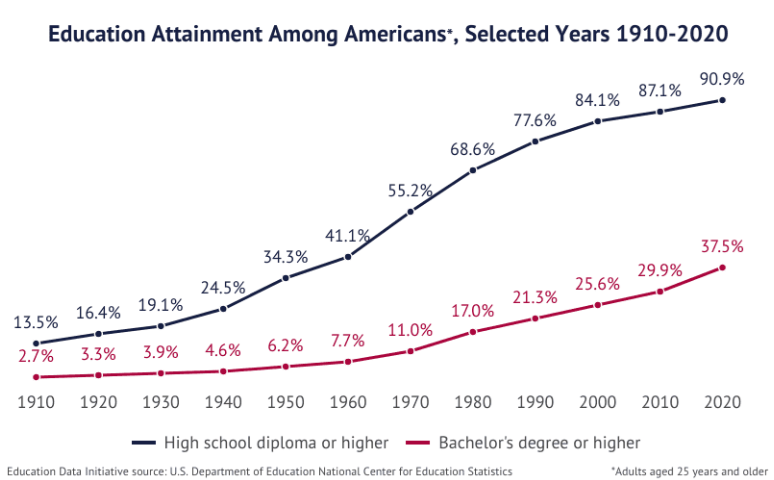

The American public has undergone a remarkable transformation that our political institutions have failed to recognize or accommodate. Over the last century, Americans have become phenomenally better educated, with high school and college completion rates rising dramatically and access to information expanding exponentially. This educational revolution has produced citizens who are less deferential to authority, more confident in their own judgment, and more capable of independent analysis than any previous generation.

The internet has accelerated and complicated this transformation. Americans now have unprecedented access to data, expert analysis, and diverse perspectives on every conceivable topic. This digital revolution has made citizens more connected in some ways, enabling them to find communities of shared interest and organize around common causes with remarkable speed and efficiency.

Yet this same technological transformation has also made Americans more isolated, more susceptible to misinformation and conspiracy theories, and more likely to retreat into information bubbles that reinforce their existing beliefs. The democratization of information has not automatically produced better-informed citizens or more effective democratic participation. One-way messaging—whatever the topic—is less likely than ever to inform and educate people.

Even when they are aware in some general sense and have a general trust in government, Americans are rarely knowledgeable about the work or invested in it, because they don’t feel personally invited to weigh in or help out.

Americans certainly have the capacity to weigh in and help out: most citizens today have handled tasks such as researching products before purchasing, organizing networks of people, learning new skills, and solving complex problems in their personal and professional lives. Partly because they are not themselves involved in the work, citizens have less confidence that government agencies, elected officials, or even nonprofit organizations can solve problems effectively on their behalf.

This creates a fundamental paradox at the heart of contemporary democracy. Citizens are more capable than ever of meaningful participation in public problem-solving, yet they feel increasingly disconnected from and skeptical of public institutions. The result is a massive waste of human potential and a dangerous erosion of the social trust that all forms of democracy require.

The rise of competitive authoritarianism

Into this vacuum has stepped a new type of government that poses an existential threat to democracy: competitive authoritarianism. Unlike the totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century, competitive authoritarian systems maintain some level of legitimacy through elections that are relatively free and fair. But when authoritarians win those elections, they systematically weaponize state power to restrict freedom of speech, suppress independent journalism, and hinder effective political opposition.

This model has proven remarkably successful across diverse cultural and economic contexts, from Hungary to Turkey to Venezuela. Competitive authoritarians understand that they don’t need to eliminate elections: they just need to tilt the playing field sufficiently to make electoral defeat less likely.

The appeal of competitive authoritarianism lies partly in its promise to cut through democratic inefficiencies and deliver results quickly. Authoritarian leaders present themselves as decisive problem-solvers who will bypass gridlock, ignore special interests, and focus on what really matters to ordinary citizens. They flood the field with misinformation. They offer the tantalizing prospect of effective governance without the (supposedly) messy complications of genuine democratic participation.

Of course, the promises of competitive authoritarians prove hollow in the end. Authoritarian leaders consistently fail to deliver on their commitments to better problem-solving and greater liberty. Instead, they typically produce corruption, economic stagnation, and the systematic erosion of individual rights. Eventually, the initial appeal of authoritarian efficiency gives way to the reality of authoritarian incompetence and abuse – but by that point, the impacts on free speech, journalism, and opposition parties can make these regimes very difficult to dislodge.

The self-defeating progressive response

Why, then, does competitive authoritarianism appeal to people who really ought to know better? Authoritarians win partly because of the responses they trigger in political elites on both right and left.

Today’s progressives, like their predecessors in the early 20th century, emphasize voting as the essential political task. They organize voter registration drives, mobilize turnout operations, and focus energy on electoral campaigns. When democratic institutions come under attack, progressives rally supporters to “Save democracy!” through the ballot box. This one-way message implies that democracy is a static system; it is a defense of the status quo.

This stance is a problem for the anti-authoritarian forces, since the status quo is not popular. Political elites—on both left and right—have not given citizens a central role in decision-making or problem-solving between elections. They treat citizens primarily as voters rather than as ongoing participants in democratic governance. And for the most part, Americans don’t feel that this system is providing the economic opportunity or quality of life they want. The call to “Save democracy!” fails to inspire voters when the democracy being saved doesn’t seem to work effectively for ordinary people.

By limiting citizen participation to periodic voting, democratic institutions fail to tap into Americans’ growing capabilities and desire for meaningful engagement. Citizens are treated as passive consumers of government services rather than active participants in democratic problem-solving. This passivity makes democratic institutions more vulnerable to authoritarian attack and less capable of effective governance.

AI: Aid to democracy or weapon of the state?

At the same time that democracy is being reduced to a simplistic yes-no question, the rise of artificial intelligence has further complicated the picture. AI could be a transformative resource for democracy or an appallingly effective tool for authoritarians. Generative AI is rapidly becoming integral to how governments work and how public problems are solved, creating both unprecedented opportunities and serious dangers.

On the positive side, AI has the potential to fundamentally reimagine the relationship between citizens and democratic governance by creating direct, personalized, and meaningful connections that help people meet daily needs. Rather than forcing citizens to navigate complex bureaucracies or decode arcane policy language, AI-powered bots and interfaces can serve as intelligent intermediaries that understand individual circumstances, translate between citizen needs and government capabilities, and facilitate genuine participation in public problem-solving. For example, bots can instantly connect parents with after-school programs for their kids, and with other parents facing similar challenges, and with opportunities to contribute their insights to help improve services. AI can help small business owners understand which regulations apply to them, connect them with relevant support programs, and enable them to share their experience with policymakers in ways that inform policy.

This vision extends far beyond improved government websites or chatbots. AI could create dynamic, personalized civic engagement experiences that help citizens understand how public decisions affect their lives and give them meaningful ways to influence those decisions. It could facilitate large-scale deliberation by helping diverse groups of citizens find common ground, surface shared priorities, and develop workable solutions to complex problems.

This represents nothing less than the potential foundation for a more effective and popular form of democracy—one that treats citizens as partners in problem-solving rather than passive recipients of services. Instead of the current system, where most civic engagement happens through crude mechanisms like elections or public comment periods, AI could enable continuous, sophisticated collaboration between citizens and their governments.

But AI also poses threats to democratic governance that we’re only beginning to understand. Automated decision-making systems can embed bias and eliminate human judgment from crucial determinations about citizens’ rights and opportunities. Surveillance technologies can enable authoritarian control that surpasses anything previous dictators could imagine. AI-generated misinformation can undermine the shared factual basis that democratic deliberation requires. Overall, AI can manipulate rather than empower citizens, creating the illusion of participation while actually concentrating power in the hands of those who control the technology.

Setting the template for future problem-solving

To navigate this transition successfully, we must learn from both our democratic past and contemporary innovations in civic engagement. The Progressive Era of the early twentieth century offers valuable lessons about how democratic societies can adapt their institution—and their professions and technologies—to fit the needs of the day.

The Progressive Era’s most enduring contribution may be its systematic approach to developing public-facing professions. During this period, reformers established the foundations of modern city planning, professional policing, city management, social work, and other fields that directly serve citizens. They didn’t simply create new job titles, they developed comprehensive frameworks that defined the skills, qualifications, and ethical considerations for each profession.

This professional development model offers a crucial template for integrating generative AI into government and civic engagement. Just as Progressive Era reformers recognized that effective public service required more than good intentions—it demanded specific competencies, ethical standards, and accountability mechanisms—we must approach AI deployment with similar rigor and intentionality.

The development of city planning provides a particularly relevant example. To elevate planning as a vocation, the planners of the early twentieth century established educational requirements, professional associations, codes of ethics, and review processes that helped ensure planners served the public interest rather than narrow private interests. This set of supports reflected a vision of how the model planner should think and act.

Similarly, the integration of AI into democratic governance has to be based on models for how bots should “think” and “act.” It requires clear standards for how these systems should interact with citizens, what qualifications their designers and operators should possess, and how they should be held accountable for their decisions and recommendations. We need to define the ethical obligations of AI systems in public service, establish review mechanisms for algorithmic decision-making, and create ongoing education requirements for public servants who work with these technologies.

The Progressive Era model also suggests that effective public-facing AI requires hybrid approaches that combine technological capabilities with human judgment and community engagement. Just as professional social workers use both technical knowledge and interpersonal skills to serve clients effectively, AI systems in government will need to integrate data analysis with a genuine understanding of human needs and democratic values.

Emerging principles for twenty-first century democracy

The most successful contemporary examples of civic engagement reveal principles that can guide this adaptation. These emerging approaches build on Progressive Era principles while adapting them to contemporary capabilities and expectations.

Four key principles are evident in this work:

Community-Centered Participation replaces the old model of official public meetings with strategies that meet citizens where they are. Rather than expecting people to attend evening meetings in city halls, effective civic engagement should happen through digital platforms that fit into people’s daily routines, trusted community connectors who bridge between neighborhoods and government, youth advisory boards that give young people meaningful voice in decisions that affect their futures, and interactive processes like citizens’ assemblies that enable genuine deliberation on complex issues.

Collaborative Governance recognizes that government agencies are no longer the only—or even the primary—problem-solvers in most communities. The most effective approaches now coordinate the efforts of nonprofits, businesses, faith communities, schools, universities, and citizens themselves around shared priorities. This might involve comprehensive plans that assign specific tasks to different organizational actors, partnership agreements that pool resources toward common goals, new financing structures that combine public, private, and philanthropic funding, and volunteer-driven efforts that help citizens contribute directly to public priorities like environmental conservation or neighborhood improvement.

Measurable Progress harnesses twenty-first century tools to make public improvement visible and accountable. Unlike the limited measurement capabilities of earlier eras, today’s approaches can engage citizens directly in measuring progress, analyzing data, and advocating for evidence-based solutions. This includes ambitious measurable objectives for multiple types of organizations, citizen-led audit programs that generate data about community conditions, expert volunteers who help design better measurement systems, and public dashboards that make progress transparent to everyone.

Technology-Enhanced Transparency updates traditional principles of governmental openness for the digital age. Rather than relying solely on paper records and public meetings, contemporary transparency uses online platforms that explain pending legislation and policy changes in accessible language, televised meetings that enable remote participation, problem-reporting systems that let citizens track government responsiveness in real-time, and voter education tools that help people make informed decisions about candidates and ballot measures.

These principles suggest a path toward democratic renewal that neither retreats into nostalgia nor accepts authoritarian alternatives. They point toward a form of governance that is more participatory than twentieth-century democracy, more effective than current institutions, and more resilient against authoritarian manipulation.

The stakes could not be higher. To defeat authoritarianism and preserve our liberty, we need political institutions that harness rather than waste citizens’ growing capabilities, that solve rather than perpetuate pressing problems, and that maintain human agency and dignity in an age of artificial intelligence. The alternative—the continued decline of democratic effectiveness and the rise of authoritarian alternatives—represents not just a political failure but a betrayal of human potential on a massive scale.