What to do about voter confusion? Here's a tool.

Imagine a four-foot-by-four-foot ballot with 1,000 candidates, 19 parties, and 60 votes to distribute. That’s

Having been raised elsewhere, in North Rhine-Westphalia, I was astonished to look at ballots there. Such a ballot is possible only in four of the 16 German states, including Baden Wurrternberg, where Stuttgart is located. I had never heard of these blanket-sized ballots back when I was getting a degree in political science.

In 2019, with elections in Stuttgart approaching, my friend Simon Strobel, a software engineer, called me from the city. He wanted advice. He was working, with a small team of volunteers, on creating a series of community events to connect candidates with citizens. He sent over a sample ballot and I got completely overwhelmed. How would anyone be able to sort through this massive amount of decision-making?

I checked around, and there was no simple tool to decrease the complexity of the Stuttgart election. Without a place that bundles information about the election, searching for information on the 913 candidates on that ballot felt like a scavenger hunt. Many local parties possessed little more than a Facebook page.

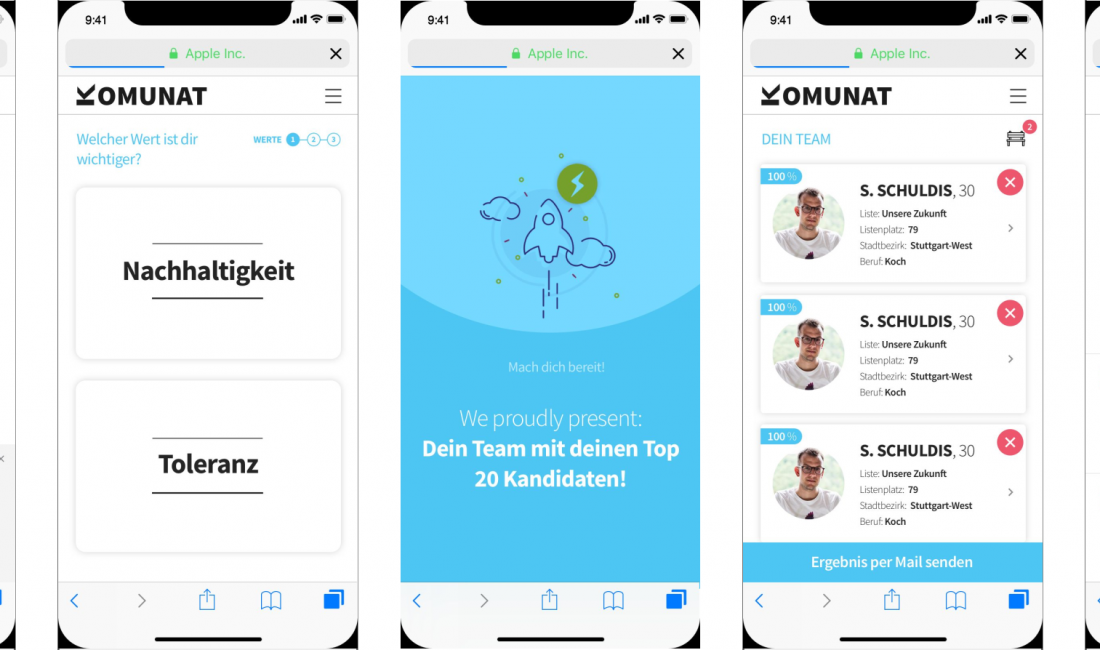

The Idea of creating a tool that could make voting more straightforward was born. The tool, now realized as

This is easier said than done, when things are as complicated as they are in Stuttgart. Why all the choices?

For starters, Stuttgart has

All this complication adds up, literally. A Stuttgart voter can cast up to 60 votes. Up to three of those votes can be devoted to just one candidate. But you can split your votes between parties and individuals, and you can move names between lists. Also, voters have to be careful in counting their votes. You get to cast 60 votes, but if you vote for one more person—a 61st—your ballot is invalidated.

The math is difficult enough that even those voters who understand the system in priniciple, struggle to manage these choices, and fill out a ballot in the way that most represents their preferences. Studies have found it’s especially hard for people to identify those candidates and parties that best fit their beliefs and policy preferences—there are simply too many parties and people on the ballot.

What we see instead is that many people choose candidates based on attributes given on the table-sized ballot: name, age, sex, occupation and party. While some voters pick only those with a doctorate, others would vote for young women. Such ways of choosing seem unlikely to demonstrate support for a political agenda

In Germany, many people cope with the complications of local elections by not voting at all. Local elections see very low turnouts, especially among the young. Only 30 percent of voters under age 30 vote in local races. Turnout is also disproportionately low among marginalized groups. Research shows these low turnouts are produced in part by ballot complexity, according to the University of Stuttgart political scientist Angelika Vetter. Another factor is the low levels of power among local parliaments, compared to regional parliaments and the federal one.

Our vision for VOTO was a tool that could sort through the thousands of candidates and dozens of parties based on the political beliefs of the user—and then suggest a short-list

What we were doing wasn’t totally new. Digital tools to spark interest in elections, to make information accessible, and to compare party positions on a set of political issues have been around as long as the Internet. And the first paper-based versions of so-called Voting-Advice-Applications (VAA) were invented in the Netherlands more than 30 years ago. Especially in northern Europe, similar guides and tools are provided by universities, NGOs, newspapers, and even governments for important races. For national elections, the German government sponsors the popular “Wahl-O-Mat,” a voting-advice-application that reaches one-quarter of the electorate.

But effective software software tools for local races and municipal elections were limited or costly. At first, we did not find funding to create them.

We asked ourselves: How would a tool look that compares all these hundreds of candidates? And what is the most relevant information for voters? Our answer at the time was: values and policy positions.

The concept was for both voters and politicians to answer a short survey. What is more important: human rights or security? The new public pool or funding for the opera? The answers would be compared by an algorithm

Thirty days before the

More than 22.000 people used our prototype to compare 913 candidates. We received considerable positive feedback.

This satisfactory, if rushed, debut encouraged us to further the development of the tool to something that could be used in any city. With the help of the German Ministry for Economy and Climate, and the Robert Bosch Foundation, we would go on to develop an open-source software platform that can be used to provide information on any election.

With VOTO, organizations can now create a VAA without requiring any technical knowledge, making the tool far more accessible. This allows us to bring down the cost of using VAA considerably. While the German government’s “Wahl-O-Mat” runs on a six

Finding the right questions to ask politicians and voters remains the most difficult part of a project. The issues posed in surveys need to be divisive enough to produce meaningful differences between parties. At the same time

We now face

Research on the benefits of VAA suggests they may increase turnout rates by up to six percentage points. (There are disputes about methodologies in such research). Most noticeably two-thirds of

Since 2019

Here is a link to the platform if you’d like to see it:

Julius Oblong is a co-founder of VOTO.