it grows strong in hard ground

BY JOE MATHEWS

Sadly, we live in a world where there are always high officials, powerful interest groups, rich companies, and billionaires who think they can govern us and our local communities better than we can.

On such a planet, seeking to govern yourself requires skill and courage. But most of all, it requires a rebellious spirit.

Local democracy, that most accessible level of self-government, is a form of rebellion. Which is why local democracy shows up in all kinds of places, many of them un expected.

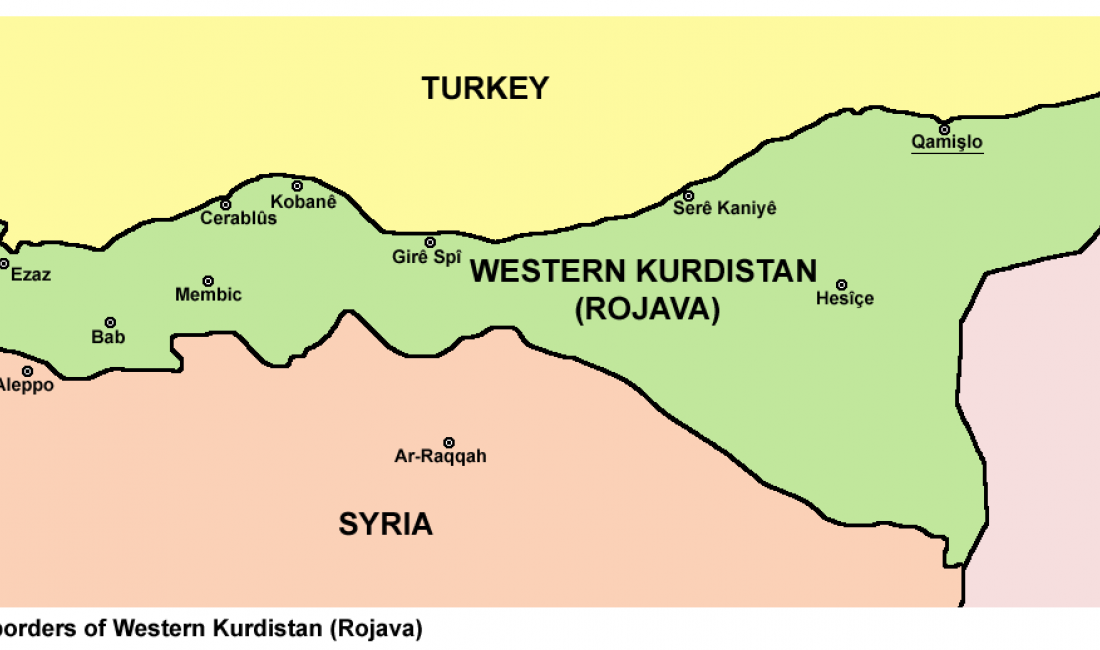

Like the border of Turkey and Syria.

How? That’s a long story, but the short version is this. The Syrian civil war displaced many Syrians from Aleppo, who ended up in northern Syria, near the border with Turkey. In response to this, Turkey intervened, through an operation called Euphrates Shield, to protect these migrants along its border. The Astana Peace Process, which involved Iran, Russia and Turkey, created a commitment to enforce a ceasefire on the border.

That relatively peaceful space was filled by self-governing cantons, or provinces. In northwest Syria, these cantons were protected by Turkey. In northeast Syria, territory was controlled by the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces and its civilian wing.

These cantons are self-governing and are likely to remain so, the Carnegie Endowment in a recent report. The most interesting and democratic of the border is the Kurdish autonomous region, known as Rojava.

Rojava includes three cantons. Afrin Canton in the West, Kobane Canton in the center, and Cizre Canton in the East. Democracy flourishes. In Kobane, for instance, there are neighborhood councils made up of everyday people. Gender parity is a rule. In a typical council, eight people—four men and four women, with one man and woman for each of four urban areas—serve on the council. councils. They can act on a variety of issues: peace, self-defense, education, sanitation or health. These neighborhood councils also inform the elected city councils of neighborhood issues.

Rojava is not some democratic ideal. Poverty and violence are facts of life, and aggressive security forces are all to present (In one recent case, security forces appear to have abducted a journalist), Threats about from the Syria government and from Turkey. But Rojava also demonstrates that democracy is possible even in conflict.

So, if you live a more comfortable place than Rojava, and if your local community doesn’t give you significant power to govern yourself, Rojava’s example asks you a question:

What the hell are you waiting for?

Thinking about local democracy this way reveals its importance. Local democracy involves small matters, but local democracy is not small. It’s the most common level of democracy.

And it is democracy’s acid test.

Whether you live in a democracy is not determined by whether your national leader accepts election results. You live in a democracy when local communities can self-govern, and go their own way.

Of course, when your community has the freedom to go its own way, that freedom will be challenged.

Which is why you can never stop rebelling.

Just look at Indonesia, with one of the most diverse and decentralized democratic systems in the world.

When the old Indonesia constitution was amended at the end of the 20th century, one crucial new provision was Article 18, a decentralization measure to defend against authoritarianism. Article 18 is one of the strongest protections of democracy in the world—because it gives the regions significant autonomy and powers. Notably, Article 18 stipulates that heads of regional governments shall be elected democratically. And localities under them, the same.

Article 18 helped spawn a diverse array of local governance, down to the village and hamlet levels, with mixes of in-person gatherings, digital tools and policymaking by the people themselves. Nearly one quarter of academic papers on local democracy in English come from Indonesia.

But now, Indonesia’s local democracy—and thus its democracy—is backsliding. Why? Because the Ministry of Home Affairs has been replacing, behind closed doors, elected regional leaders who leave office with appointed interim regional heads, some from the military. This violates the constitution. And these interim heads have often pushed down, to replace local leaders.

Decentralization and democracy are related, but not exactly the same thing. Nation-states can be called democratic even when their heavy centralization means there isn’t much local democracy. France, whose president calls himself “Jupiter,” is an example of that.

On the other hand, authoritarian or one-party nation states can contain robust local democracy. Many Turkish cities are leaders in democratic participation and practice, even under an increasingly authoritarian national prime minister. Or take Vietnam, where the non-democratic government has decentralized authority to a degree where many provincial and local governments display remarkable flexibility and innovation. Because officials, at least in certain areas have authority to borrow, contract and regulate.

When a central government is rich and powerful, even in democratic places, it can be hard for everyday people to govern themselves. I’m from California, a rich and free place that thinks it is quite democratic. But we have a state governing system that centralizes power in the governor, and at the state level. Our localities are weak, and lack authority over their own finances.

So, the most successful places in self-government are not SF and Los A/ngeles—the state is watching them—but smaller places that can break the rules, like West Sacramento, population 50,000. Perhaps the most democratic city in California is a town of fewer than 10,000 people—Gonzales, in our salad bowl of the Salinas Valley—that goes its own way.

Gonzales found ways around the rules of higher-level governments to create its own health infrastructure, to build out clean energy and attract new business, to provide higher levels of child care, and to give more democratic power to its people, including children.

Coming up with those solutions required the engagement of everyday people. Just as with any successful rebellion.

This piece was adapted from a speech given at the International Day of Democracy conference, organized by the Swiss Democracy Foundation in Bern.