First of three excerpts from International IDEA's Stockholm Series of Public Lectures on Climate Change and Democracy.

This is the first of three excerpts from Greta Ríos's lecture. “The promise of participation – How collective decision making can get us to more effective climate policies." It is part of "The Stockhom Series on Climate Chagne and Democracy," from International IDEA. This lecture took place on November 12 at International IDEA’s headquarters at Strömsborg in Stockholm, Sweden. (Photo credit: People Powered)

My name is Greta Ríos, and I am the Co-Executive Director at People Powered, a global hub for participatory democracy.

Today I am standing in front of all of you because a decade (or so) ago I fell in love with an idea that I came across on a subway train in my commute to work in Mexico City. This idea was simple: the city was going to let citizens have a say in deciding how to spend a part of the public budget by allowing them to present project proposals and vote on them for implementation.

It must have been around 2013 or so when I learned about the polling stations for neighborhood projects that would be set up in that subway station the following Sunday. I had returned to Mexico City after spending some time abroad, and I had no clue what these neighborhood projects were about.

At that time, I was in my third year as founder and Executive Director at Ollin, a Mexican non-governmental organization (NGO) focused on democracy and the rule of law. One of Ollin’s areas of interest was youth inclusion in democracy and social change, so the idea of these neighborhood projects was really appealing to me. Later that evening, I spent some time learning about the neighborhood projects and how participatory budgeting, which was the technical name for them, worked.

I did not know it back then, but that poster changed my life for the better. Ollin ended up developing expertise on participatory budgeting: we created the first website to track the progress made by the projects, participated in creating a new legislative framework to make the process smoother, and evaluated other experiences of participatory budgeting in several cities in Mexico.

Why participatory budgeting? Mexicans, like the citizens of many other countries around the world, have fallen out of love with democracy. Not only did they have to struggle for decades to get some sort of democracy in place, but this shiny new system failed to deliver on most of the things it had promised us. It is not a surprise that most Mexicans feel no excitement about going to polling stations or getting involved in political affairs.

But participatory budgeting offers new insights into democracy on at least three different fronts. The first one has to do with how long it takes for you to actually see results. Spoiler alert: it does not take long. From the moment you vote on your favorite proposal to the actual execution of the winning project, just a few months go by. In Mexico City, for example, citizens go to the polling stations in May, and projects must be concluded by the end of the year. This makes it easy to track the whole process, from promises to execution. Thanks to Ollin and other entities, it is now possible to track the projects that have been selected per neighborhood, as well as the costs associated with them and their completion status.

This brings me to the second insight: participatory budgeting is a great way to use democracy to teach people of all ages about fairly abstract and quite technical concepts, such as public procurement, public budgets, fiscal transparency and accountability. It is really encouraging to be able to track the transformation that happens when citizens go from being amateur democracy enthusiasts to understanding in depth how public projects should unfold, from start to finish. And the fact that participatory budgeting teaches this through experience and, in a sense, gamification makes it even stronger because it is always easier to learn something by doing than by sitting in a classroom and just reading about a concept that is absolutely foreign to you.

The third aspect is the most important. It has to do with the sense of agency that this sort of process conveys to the people who participate. It is truly

transformative knowing deep inside you that you are able to change things in your neighborhood to make it better and that the way to get there is by talking to your neighburs, by creating visions of your street together, by doing research on the legal status of that piece of land that has been abandoned for decades—in a nutshell, by making democracy work for you. I believe that people who have become involved in participatory budgeting also become more active in their communities. And now they even have the tools to do so: they are known in their neighborhoods as leaders, they have direct contact with the local authorities, they understand some of the problems of the community, and they know at least of one mechanism that they can use to solve those problems.

These three components (the visible and quick effects of the process, the pedagogical component and the creation of agency among the population) are present not only in participatory budgeting but are common effects of participatory democracy processes in general. You see,

participatory budgeting is part of a broader family of innovative democracy practices around the world that

have the ultimate goal of getting more people to participate in decision making, along with their governments, on things that affect their lives.

During this talk, I will discuss some of the mechanisms that are used in the field of participatory democracy and, in particular, their effectiveness for tackling climate change.

This is my first story.

In 2022 the Ollin team worked in the state of Hidalgo, with the community of Santa Ana Tzacuala, in the municipality of Acaxochitlán. This is an Indigenous community of 5,000 inhabitants, where local customs and traditions reign and permeate the political structures as well as citizens’ understanding of their civic duties and belonging.

When you enter this very small town, it is evident that it is a tight-knit community and that the inhabitants hold their traditions really close to their hearts. Women in Santa Ana wear traditional clothing, woven and embroidered locally. Santa Ana’s main economic activity is the flower trade: locals buy flowers from nearby producers and then resell them. This means that many of the people who live in this community are not usually around during weekdays. The town is also known for its high emigration rate, especially among young males. The number of 5,000 inhabitants is actually an estimate because it is really hard to keep track of the population under such conditions.

In Santa Ana there is a traditional representative body that acts as the highest authority when it comes to taking decisions that have a direct impact on the community. This body, known as the ‘delegation’, is made up of four people who have strong bonds with the community and are elected to serve a full-time one-year term with no remuneration. It is a great honor to serve on this body, and this job is taken with the utmost seriousness.

The members of the delegation were the first brick wall I bumped into when my team and I were trying to convince them to take a leap of faith and engage in a project to expand democracy in Santa Ana by running a pilot participatory budgeting program in the community.

Picture the following: it is the early afternoon on a very foggy day in Santa Ana when Karla, a 24-year-old democracy enthusiast, and I arrive to have our first hearing with the delegation. We have no clue what to expect or how to address this group of older and very conservative men, and we are also the only two people in the room wearing face masks, as there is a high number of Covid cases in town, and we are both afraid we might catch it. We then spend more than three hours going back and forth, discussing the project’s specifications, the reasons why we think it’s a great idea and how we would devote almost a full year to training and working with the community to design and run the pilot until the winning projects are fully delivered

It is very evident that both the delegation and my partner and I are out of our comfort zones. The all-female team in Ollin is more used to working with audiences that look and speak a bit more like us. The all-male, all-middle-aged delegation members are also not used to speaking to women, least of all to young women who come unaccompanied to.present projects at the town hall. We left Santa Ana very late that day without a concrete reply on their part and also with a lot of doubts in our hearts. The fact that it was a super dark and rainy night did nothing to help our mood.

But, apparently, the saying ‘after the storm comes the sun’ is correct. Luckily for all, after a few days we received a call from the delegation saying they approved of this collaboration. This was the beginning of a series of visits to Santa Ana, during which we truly fell in love with the community and with its people.

The Ollin team spent the following six months working with the Sanataneros (this is how they refer to themselves) to set the rules of the process, but also to train relevant actors on how participatory budgeting works. They made sure that women had seats in the decision-making bodies, and they also pushed for children to be able to participate in the process. Both requests were granted, and some very easy actions were taken to make

sure that these two groups were represented throughout the process.

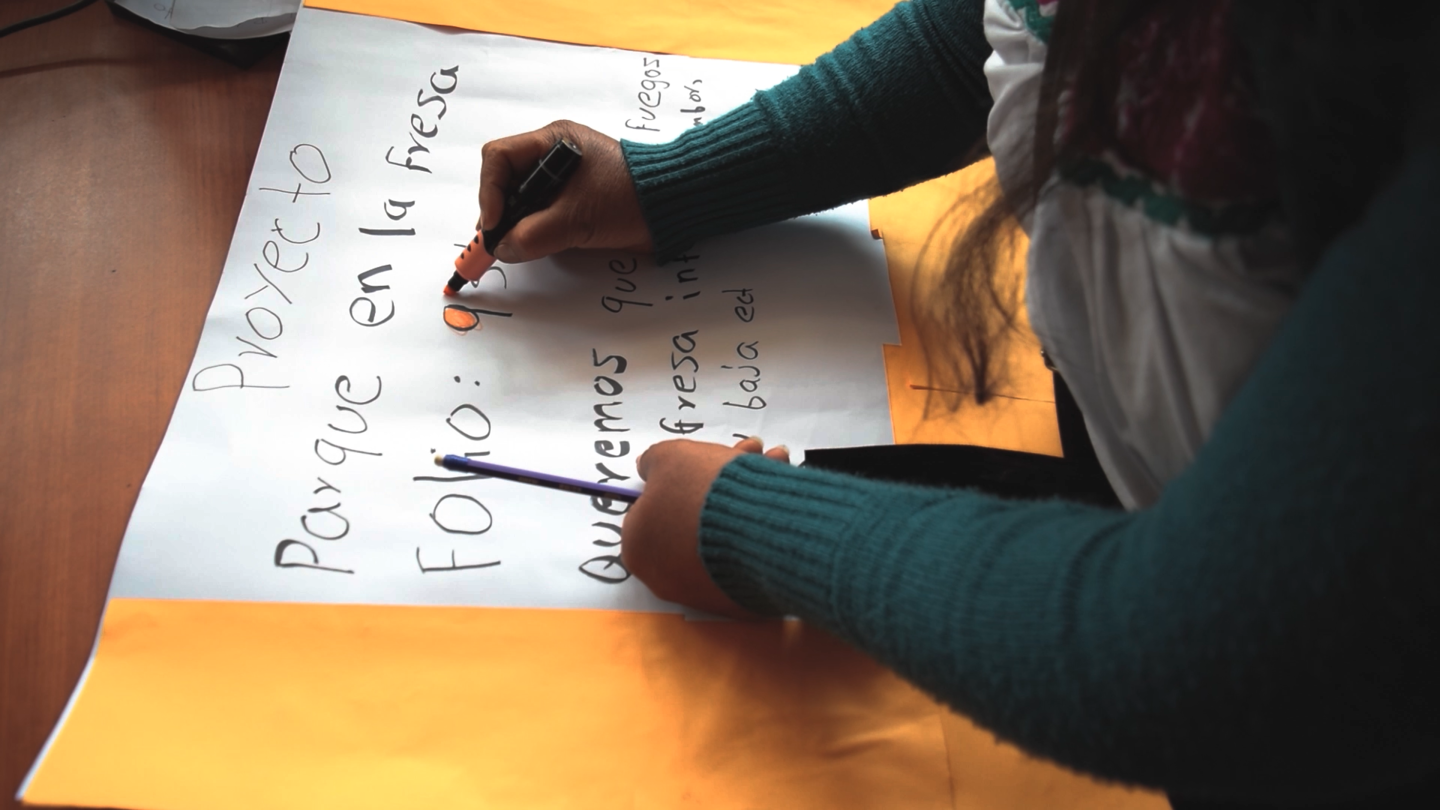

One of the actions consisted in bringing the training sessions on participatory budgeting to the schools so children could learn about the process and start thinking about their options for voting. I absolutely love participatory budgeting sessions with children because they are so used to being left out that when you tell them they will be able to present proposals and vote in the process, their first reaction is always disbelief, but their

second reaction tends to be joy and empowerment and agency. This is what we were going for.

The people of Santa Ana decided that children aged 10 and up were eligible to participate in the process. The reason they made this decision had to do with the fact that, when a child in the community turns 10, they are required to start providing the community with services like mowing the grass or cleaning up common areas because they are part of the community. The logic applied here was that if they were old enough to be accountable to perform these tasks, they should also have the right to fully participate in the democracy project.

The Ollin team spent many hours at the local middle school, getting to know these children and talking to them about the problems facing their community and seeing them come up with creative solutions to these problems. At the end of the process, two of the three winning projects were proposed by children and youth, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. I will tell you more about the winning projects in a bit.

Getting the women involved was a bit harder, but it was not impossible. ‘We just met them where they were’, was the explanation the Ollin team gave me when I asked how they had managed to get the women to participate. They went to public parks, the church atrium and the community gardens, where women normally congregate to weave together while they talk to each other and take care of their children. The third winning project was proposed by a mother of two young kids. In her project proposal, she asked for a playground where the kids could play safely while the women could weave and look after them.

But let me go back to the children and youth and introduce you all to Heidy, who is a living prototype of the citizen we want to empower and make sure they stay engaged for life.

Heidy is a 12-year-old Indigenous girl who lives in Santa Ana. She found out about the participatory budgeting pilot when the Ollin team went to her

school to invite the children to participate. Heidy had been concerned about the environment for some time, and she saw thisproject as a great opportunity to do something about it. She had heard from her grandfather that, many years ago, there had been a dense forest in Santa Ana, but that

this forest had burned down in a wildfire and had not succeeded in regrowing on its own.

With this in mind, she proposed a reforestation project where she and her classmates could help plant trees and take care of them so they could bring the forest back to Santa Ana.

It was a great victory for Heidy, but also for the community, because the project was designed in such a way that it increased the chances that these trees would survive. What Heidy’s school did was adopt the trees and water them and take care of them regularly. This is a great example of community action to mitigate climate change, carried out by using participatory budgeting.

Through this project, the schoolchildren learned about negotiation, project management, climate change and civic engagement. They also learned that they could tackle the problems of their community in innovative ways and that the adults could follow their lead. In 2023 Heidy was awarded the State of Hidalgo Youth Award for her contributions to her community and as a recognition of her leadership skills.

Some unintended but really welcomed consequences of this project were the following: The participatory budgeting voting process saw more than twice as much participation as the previous official democratic exercise in the community.

1. In 2024 a woman was appointed as part of the delegation for the first time in the town’s history.

2. Nearby communities passed legislative acts that allow them to have participator budgeting processes.

3. Others have asked for technical assistance to replicate this process locally.