On December 2, 1766 Sweden was the first country worldwide to replace the principle of amnesia with the freedom of information. It was an important first step towards modern democracy, reports Bruno Kaufmann.

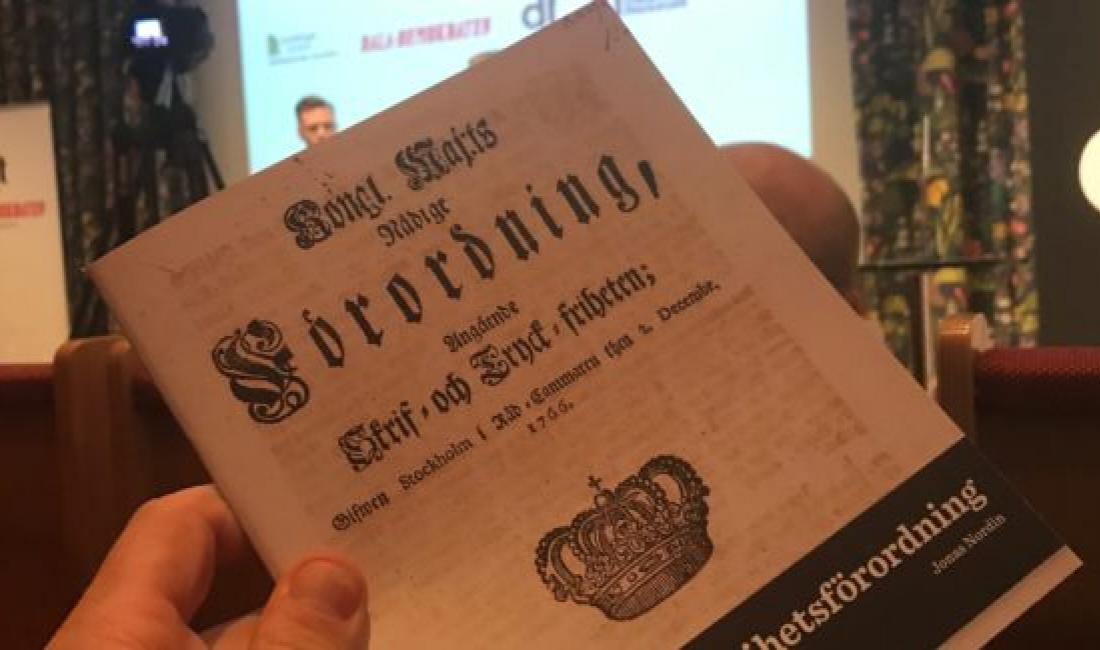

The other day I found myself at a museum in my hometown Falun. Here, in the middle of Sweden, 250 kilometers north of Stockholm, I gathered with fellow journalists and citizens to celebrate the big anniversary of the Swedish Freedom of Information Act ("Tryckfrihetsordningen"). I felt the ambivalence of the venue, Dalarnas Museum. Was the birthday child, after all, something of the past? In fact, the original freedom of information act, can be seen as the single most important Swedish contribution to modern democracy. A freedom however which "is under attack and needs to be defended and developed at the same time", Carl-Johan Bergman, Editor-in-Chief at the local newspaper "Falu Kuriren", said in a opening panel with investigative journalist Björn af Kleen, who has written several well-known books around the issue.

Inspiration for a whole world

Sweden passed its Freedom of Information rule 250 years ago, under an otherwise absolutist king. It was a constitutional principle, adopted by the Swedish parliament that made this plain:, nobody could be indicted for something he or she had published, before it was published. With those words, Sweden became the first country in the world to constitutionally abolish censorship a quarter of a millennium ago. This initial Swedish Freedom of Information act inspired a whole world. And it endured, even as unelected monarchs continued to hold power (until 1974). And after the second world war, the act´s principles were modernized to include extensive freedom of speech rights as well as a very comprehensive right to request public documents: today for example everybody has the right to see the incoming emails of an elected official or a public servant.

But the right of free information, despite its long history, remains highly contested, a point made at anniversary celebrations in Falun and many other places across Sweden. One reason is, that Swedish courts still stick to the original principle of the "tryckfrihetsordningen" (literally "freedom of [printed] press act") and use different judgment, when it comes to online publications. Second, political authorities have developed interesting strategies to exclude public documents form the public - by declaring them national secrets or private-public negotiations excluded from the Act.

As a result, many individuals struggle to claim their rights to information. And many independent media, now fragmented and journalistically weaker, have had difficulty demanding information under this law. This is reflected in the quality o the press.In my hometown Falun, the two local newspapers do now have the same owner and offer a lot of similar content. As the traditional business-case for such publications is disappearing, professional journalism is losing ground, while online media resources are focusing on creating attention (and cklicks) by (partly unjustified) headlines - or serve very exclusive circles.

Signs of erosion

The bleak picture goes beyond journalist. Some 250 years after an early and genuine breaktrough for democracy, Sweden faces great challenges. According to an article in the Journal of Democracy, there are signs of significant erosion in Swedish democracy and in other established democracies. The trouble: citizens see democracy as less desirable, and some prefer authoritarian arrangements. "Here the percentage of people who say it is "essential" to live in a democracy has plummeted, and it is especially low among younger generations", says German political scientist Yascha Mounk, which I met a few weeks ago in Berlin. So happy birthday Swedish Freedom of Information Act. But try not to end up in a museum, please!

Bruno Kaufmann is a journalist and political scientist based in Falun/Sweden, where he chairs the Democracy and Election Commissionof the City. He is the author of the European Passport to Active Citizenship(available in 22 languages) and editor at people2power.info.