John Conness was an Irish immigrant who stood up for citizenship and human rights. His words still matter.

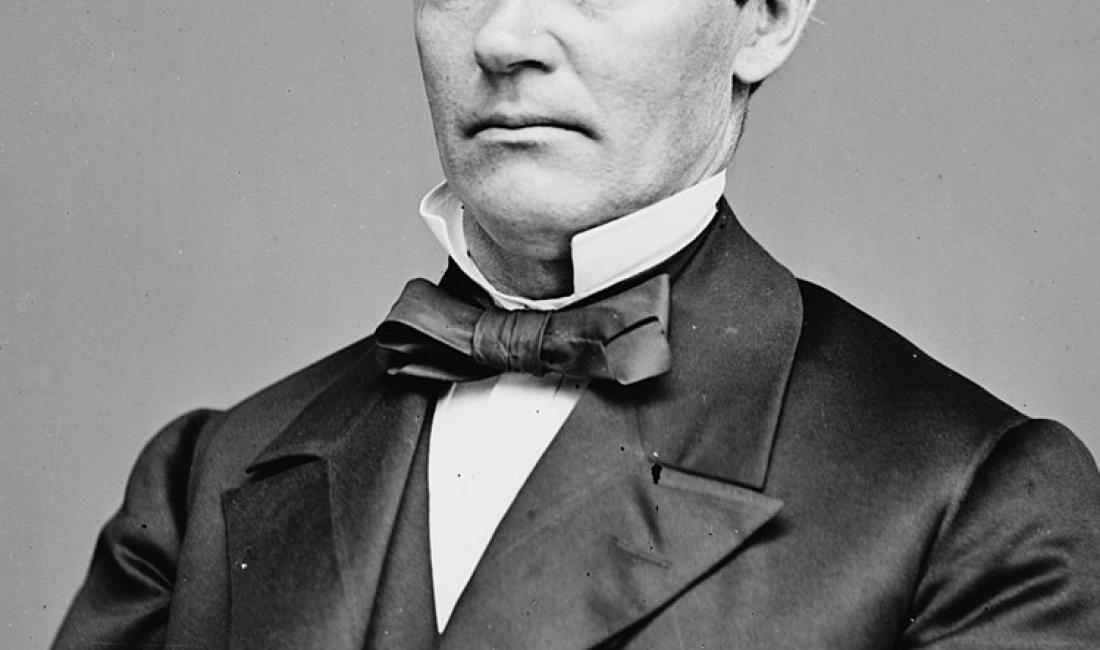

This column is co-published with Zócalo Public Square. Photo of John Conness by Matthew Brady in the public domain, via Wikipedia and the Library of Congress.

John Conness still represents us. And how lucky are we for that!

So what if few Californians, and not even many California scholars, have ever heard of him? Nor does it matter that Conness hasn’t served in public office since 1869.

Because, right now, John Conness, and words he spoke in the 1860s, might be the best weapons California has against the new U.S. dictator/president—and against his lawless plans to deprive children born here of their constitutional right to citizenship.

Conness, who represented California in the U.S. Senate from 1863 to 1869, was clear and outspoken in support of birthright citizenship when Congress passed the 14th Amendment.

And Trump’s attempt to end birthright citizenship is based on falsely rewriting the text and history of the 14th Amendment—the very history in which Conness was player. While the amendment’s first section says plainly that “all persons born in the United States” are citizens, Trump claims the amendment was never intended to include everyone.

In his January 20 executive order declaring an end to birthright citizenship, Trump suggests that the amendment was only meant to ensure that former slaves of African descent had citizenship. The amendment, the order says, “has never been interpreted to extend citizenship universally to everyone born within the United States.” Trump claims that Congress never intended to entitle the children of immigrants without permanent legal status to birthright citizenship.

And if Trump can convince the conservative U.S. Supreme Court to accept his claims about this history, birthright citizenship could disappear.

So it is now important that, way back in 1866, Conness preemptively put the lie to Trump’s claims. The California senator led the debates that produced the 14th Amendment. And he constantly turned aside proto-Trumpian demands from his Senate colleagues to exclude some groups.

In late May 1866, when Pennsylvania Sen. Edgar Cowan suggested excluding from birthright citizenship “Gypsies,” “Australians,” “people from Borneo,” “man-eaters,” “cannibals,” or “another people of a different race, different tastes and sympathies,” Conness and made the intention behind the proposed amendment clear:

“Here is a simple declaration,” he said. “Human beings born in the United States shall be regarded as citizens of the United States, entitled to civil rights, to the right of equal defense, to the right of equal punishment for crime with other citizens. And that such a provision should be deprecated by any person having or claiming to have a high humanity passes all my understanding and comprehension.”

In the debate, Conness frequently referred to Chinese immigrants in California, a deeply unpopular minority. The senator acknowledged that many Chinese people lacked rights and had been brought here illegally, under enslavement-like “coolie contracts.” Whatever his Congressional colleagues thought of those migrants, Conness stated, their U.S.-born children were Americans.

“The children of all parentage whatever, born in California, should be regarded and treated as citizens of the United States, entitled to equal civil rights with other citizens of the United States,” he said.

Conness’ words should carry special weight now because he, like us, was living in an era of constant emergency and bitter conflict, when lies and bigotry seemed to overwhelm the truth. And his personal story deserves better notice, because it reminds us that, in difficult times, we must listen not to the most popular people, but to those who express timeless principles born from struggle.

John Conness was himself an immigrant. The 14th of 14 children, he was born in 1821 in County Galway, Ireland; his family immigrated to New York as a teenager. In 1849, at age 28, he headed west to seek gold in California. He opened a successful store, selling supplies to miners, in the small settlement of Georgetown in El Dorado County.

He had little interest in politics until the 1850s, when ruling Democrats—his own party—tried to split California into two states, with Southern California permitting slavery. “It was never my purpose to seek public office or public life,” he said, until “there were such efforts to ally California with proslavery.”

So, in 1853, the small-town businessman won a state assembly seat as an “anti-Chivalry,” or anti-slavery, Democrat. There, he was one of the “12 Apostles”—lawmakers fiercely opposed o slavery.

In the 21st century, the historian Robert Denning would call Conness “the consummate nineteenth-century California politician: bold, energetic, shrewd, partisan, sarcastic, and, as one [newspaper] account put it, ‘with sufficient pugnacious proclivities to back up his moral suasion by all his physical force.’”

But Conness never won an election above the level of the Assembly. He lost an 1856 bid for Congress and races for State Senate and lieutenant governor. And on September 13, 1859, he lost his mentor, the U.S. Senator David Broderick, the leader of the anti-slavery political machine of “Union Democrats.” Broderick was shot and killed by the Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court, David Terry, in a duel in San Francisco. Terry was a former ally who had become a Confederate sympathizer.

After Broderick’s death, Conness took over the Union Democrats and ran for governor in 1861, losing to Leland Stanford. His career appeared over. But in 1863, his Union Democrats combined with anti-slavery Republicans to form the “Union Republicans.” With his faction gaining power, Conness was appointed by the legislature to the U.S. Senate. (U.S. Senators would not be popularly elected until the adoption of the 17th Amendment, in 1912.)

In Washington, Conness embraced the Emancipation Proclamation, the repeal of fugitive slave laws, and the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and quickly grew close to Lincoln. (Conness was unusually powerful in the Senate because California’s other senator, James McDougall, was barred from all committees because of constant drunkenness.)

In 1864, Conness convinced the president to sign landmark legislation to protect the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove. Mount Conness and Conness Creek, on the edge of Yosemite National Park, are named in his honor. Conness was one of six pallbearers at Lincoln’s 1865 funeral.

During Reconstruction, Conness became known for supporting civil rights, and especially the rights of Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans.

When a Michigan Democrat objected to 14th Amendment protections for Chinese people, Conness explained [SR1] that these immigrants were vital to California and its economy: “They are a docile[SR2] , industrious people, and they are now passing into other branches of industry and labor,” Conness said.

But back in California, the anti-Chinese movement was growing. In 1868, the California legislature refused to ratify the 14th Amendment precisely because it provided citizenship and equal protection of law to Californians of Chinese heritage. California finally ratified the amendment in 1959.

Conness, deeply unpopular for his inclusionary racial views, retired from politics at the end of his term in 1869. He moved to Boston, with its thriving Irish community, and died there in 1909, with little notice.

But Conness’ life demonstrates this truth: What we do and say now, as national leaders attack our constitutional rights, may matter not just today but in centuries to come.