An inmate writes about how food connects a town and its prison.

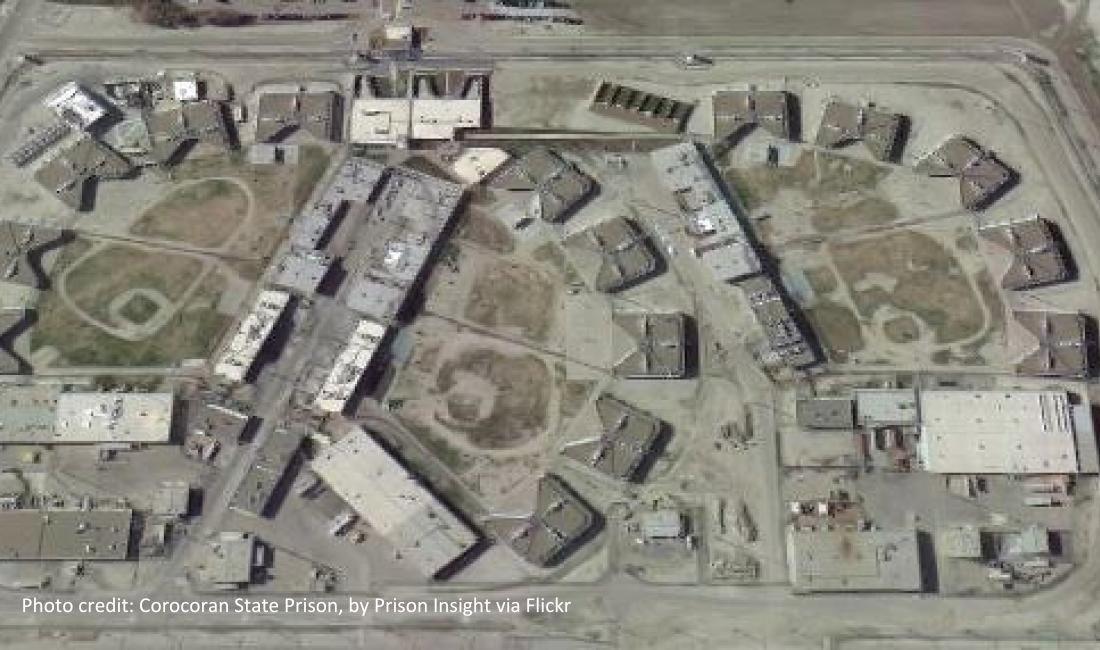

This story was originally edited by Joe Mathews and published by Zócalo Public Square in 2022. Photo credit: Corocoran State Prison, by Prison Insight via Flickr

Imagine a big box. You sleep in the box. Eat in the box. Work in the box. Exercise in the box. Your view is confined to what fits inside and a slice of the sky above. On occasion, one of the box’s walls opens, allowing you, for a short time, to step outside, where another, larger box awaits.

That’s my best attempt at describing the separation between the rest of the world, and the inmates here on C-yard at the Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison (SATF), one of the highest security yards in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. The prison’s design erects huge barriers between the inmates and the city of Corcoran, which lies outside the second “box.”

SATF opened its heavy door in 1997. Three years later, the 2000 U.S. Census found that Corcoran’s population was less than 14,500. In 2010, that number reached nearly 25,000. By 2020, the population had dropped down to 22,000. The ebb and flow largely represents the changes in the number of people who reside here inside the boxes: SATF’s inmate population reached 7,500 in 2005 and hovered around 4,500 in spring 2021.

Despite that increase since the prison’s opening, Corcoran remains a small town by California standards—a status that sets it further apart from C-yard prisoners. We rarely get to see the place. Inmates with county legal matters must travel outside the city to find a court. For medical procedures beyond SATF’s capability, prisoners are taken to hospitals in Fresno, Tulare, and Kern counties. Network affiliates are located in Fresno and Bakersfield, so the only regular reporting on TV that inmates see about Corcoran itself comes from the weather crawl listing the day’s expected temperatures. Daily life in other cities around the Central Valley is more familiar to C-yard inmates than that of the actual town in which they reside.

Over recent years, though, a connection has been slowly forged between Corcoran and some of its resident maximum security inmates. The rather benign force responsible?

Food sales and charity fundraisers.

Local vendors, C-yard’s administration, and the Inmate Advisory Council (IAC)—an elected body of inmates, by inmates, and for inmates—have partnered to make food sales to the inmate population regular events over the last four years. The food sales provide major payouts for the vendors and also benefit local community organizations. Every sale has a designated charitable recipient, which receives a percentage of the money raised.

From start to finish, each food sale requires about a month to organize. Much of the legwork falls upon the IAC representatives. Just some of their tasks include: requesting the desired food vendor; passing out, picking up and submitting food sales slips for approval; and delivering each individual order to inmates on the day of the sale.

The administration handles contact with the vendors, processes the sale slips, and determines the charity recipients. Local restaurants and franchise chains alike—offering Mexican food, Asian food, BBQ, pizza, hamburgers and ice cream—have participated. The charity recipients are rotated with every sale, though an organization called Corcoran Emergency Aid has been selected multiple times. The September 2021 sale benefited the Corcoran Kiwanis Club.

Inmates who participate in the sales know they will pay a steep price for the food. During the August 2021 sale, for example, pizzas were priced between $14 and $21. Burgers in the September 2021 sale cost $7 to $13. There is also the 13 percent obligatory donation fee, added to the top of every order.

Despite these costs, the sales are popular among inmates. The August 2021 sale generated over $19,000 in sales and $2,500 in donations, about average for these fundraisers. Considering that these sales occur nearly every month (perhaps two a year are canceled for various reasons, and five more were scrapped in 2020 due to the pandemic), the scope of the funds pumped into Corcoran and surrounding communities is staggering.

The sales also represent a significant transfer of capital from urban to rural areas. Most inmates on C-yard come from big cities in Southern and Northern California, and receive their spending money from friends and family back home.

The frequency of these food sales surprises inmates newly arrived on C-yard; such events are less common in many other prisons, where the biggest direct expenditures from inmates involve canteen and package purchases. Little if any of that money ends up in the surrounding communities. For Corcoran, where businesses and community organizations have suffered in the pandemic, the food sales supply an additional economic benefit to supplement the many advantages of SATF’s presence.

Earlier, I asked you to imagine a box within a box. Let me add some specifics. C-yard in SATF is a huge concrete warehouse anchored within a massive cage of razor wire and lethal electric fencing that puts the “State Prison” into the institution’s otherwise progressive-sounding name. Among maximum security yards in California, C-yard is exceptional for its lack of inmate jobs and outdoor recreation time. It was designed for warehousing, not programming.

Other SATF yards have afforded inmates opportunities to make a positive impact on the community through mentor and juvenile diversion programs. For years, C-yard offered essentially no rehabilitative activities of any kind. This began to change, slowly, in 2016. Self-help and educational classes increased little by little, until the pandemic shut down those programs for over a year.

Food sales only paused briefly with the arrival of COVID-19; they remain the closest thing to direct contact that C-yard inmates have with the community.

Does it matter that most inmates would rather not pay the charity donation? My own answer is to point out what is clear: that all interested parties gain from the sales. Prisoners get a needed break from prison food. Vendors receive a big dose of business. Community organizations collect critical funding gifts. Those are three big reasons why food sales are a good idea.

But food sales are only one small idea. Here’s an even better, bigger idea: every yard in every California prison, regardless of security level, should offer its inmates the opportunity to make a positive impact on the local community.

Indeed, given the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s present emphasis on rehabilitation, any project that instills in inmates the desire to help others, and the community at large, should be seen as a critical component of that process.

And, even with security dictating some limits, there is no shortage of possible ways to connect our prisoners and our prison towns. Volunteer work could take many forms, both virtual and in-person. Prisons could partner with community organizations to do work inside the prison and in the community. Certainly, the current debates in California communities about crime and punishment and related problems like homelessness would be well-served by including those who live in state-owned boxes.

In the meantime, food sales should and will continue here, until we muster the will and creativity to find better ways of transcending these prison walls.

This piece is part of the Zócalo/California Wellness Foundation Inquiry “What Would the End of Mass Incarceration Mean for Prison Towns?” and is supported by the California Wellness Foundation.