The Myanmar junta builds power with ruins. Citizens are not only ignored in the aftermath of the 7.7 magnitude earthquake of March 28 2025, but instead abused in their vulnerability, as the junta lunges for more ground among the civil war. The natural disaster has revealed that unaccountable governance has deepened the disaster’s toll. Rather than mobilising relief for its citizens, the unelected military junta—the State Administration Council (SAC), which seized power in a coup in 2021—has used the devastation as a tactical advantage. There are allegations of aid being withheld from regions where there is rebel resistance to the SAC. Civilians—already driven from their homes by civil war and now displaced by collapsing buildings—are being targeted by the military. The earthquake is not just a humanitarian crisis; it is a disaster exacerbated by authoritarian rule, and a stark reminder that, in the absence of democracy, citizens are denied a voice—especially in times of crisis.

This article seeks to highlight how natural disasters are exacerbated under authoritarian governments. It examines how the military junta has exploited catastrophe to increase authoritarian control, and how the absence of democratic governance has intensified human suffering. At the same time, this article centres the agency of Myanmar’s people, civil society, and grassroots actors who, despite violence and disaster, continue to resist authoritarianism and demand a democratic future.

By connecting the humanitarian, political, and democratic dimensions of the crisis, this article also calls for informed, conflict-sensitive responses that honour the voices and leadership of those on the ground.

Events Leading Up to the 2021 Coup

On 1 February 2021, Myanmar’s military—known as the Tatmadaw—overthrew the democratically elected government led by the National League for Democracy (NLD) and detained its leader, Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. This marked a return to full military rule after a decade of partial civilian governance. Ironically, the coup was enabled by the 2008 constitution which was itself drafted solely by the military as part of a controlled transition to a superficial form of democracy. While it was framed as a step toward civilian rule, the constitution was deliberately designed to entrench military power, reserving key ministries and 25% of parliamentary seats for the armed forces. In the end, the very legal framework that was intended to support democratic governance became the mechanism used to dismantle it.

The 2008 Constitution, the 2021 coup, and the response to the recent earthquake, align with the military’s broader strategy to consolidate control. The capacity of the military to manipulate the fabric of society stems from Myanmar’s earlier history: from 1962 to 2010, the country was under direct military rule. Although the period from 2010 to 2021 introduced limited reforms, the armed forces continued to exert political dominance from behind the scenes.

Beginning in 2016, the military intensified its persecution of the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic minority, continuing a long-standing pattern of discrimination and violence. The United Nations described these actions as an ethnic cleansing. Despite holding power at the time, Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) were widely criticised for their silence and inaction during the crisis—whether out of fear of challenging the military’s authority or due to political indifference toward the Rohingya’s suffering.

At no point during the 2011–2021 period, was the military fully removed from the structures of the state. Under the 2008 Constitution, it retained 25% of parliamentary seats, giving it effective veto power over constitutional amendments and other substantial legislative reforms. This allowed the military to operate as a powerful and unaccountable force, beyond the reach of elected civilian governance. However, this period also reflected the determination of Myanmar’s people to push for change. The 2010 general election—though heavily criticised for lack of transparency and boycotted by the National League for Democracy (NLD)—marked a transition away from direct military rule. It was followed by the formal dissolution of the State Peace and Development Council (the official name of the previous junta), a reduction in censorship, and the release of political prisoners. The 2015 election, which the NLD won decisively, was described by Freedom House as “largely peaceful” and brought the country meaningfully closer to democratic governance—thanks in no small part to the persistent efforts of Myanmar’s citizens, activists, and civil society actors striving for a more representative future.

Following the 2020 general election—won once again by the National League for Democracy (NLD)—the military falsely alleged widespread election fraud, despite both domestic and international observers confirming the legitimacy of the 2020 vote. In February 2021, the Tatmadaw launched a coup, overthrowing the elected government and detaining its leaders, such as Aung San Suu Kyi.

The coup was not a sudden rupture but rather a calculated use of legal authority embedded in the 2008 Constitution—specifically, Article 417, which allows for the declaration of a state of emergency in situations deemed a threat to national unity or sovereignty. After baselessly claiming electoral fraud, the military invoked this clause to justify its takeover. Crucially, the power to declare the emergency rested with the Vice President, a role then held by Myint Swe, a former general and military appointee. Acting within the constitutional framework, Myint Swe transferred power to the Commander-in-Chief, Min Aung Hlaing, thereby handing full control to the military.

This manoeuvre was only possible because of the military’s entrenched role within the state apparatus. Under the 2008 Constitution, 25% of parliamentary seats are reserved for military officers, and key ministries—including defence, home affairs, and border affairs—must be led by military personnel. In practice, this created a system where elected civilian governments were perpetually constrained by the institutional power of the armed forces, which extended beyond politics into the administrative, judicial and economic spheres. The 2021 coup was therefore not a breakdown of Myanmar’s constitutional order—the groundwork for it was built within the constitution itself.

The coup provoked mass protests and widespread civil disobedience, which in turn led to the formation of armed resistance groups, most notably the People’s Defence Forces (PDFs). The military regime now operates under the name State Administration Council (SAC) and continues to exert authoritarian control. However, due to the ongoing civil war and expanding resistance, Myanmar remains deeply fragmented. By chance, many of the areas most affected by the 2025 earthquake—particularly in central regions—are those currently under the control of rebel forces, not the junta.

Local civil society organisations (CSOs) in Myanmar have remained consistently vocal in denouncing the military’s abuses and asserting the political agency of the population. They continue to raise alarm about ongoing human rights violations and seek regional and international responses rooted in the realities of those on the ground. In March 2025, a coalition of local CSOs issued an open letter specifically urging the member states of BIMSTEC—the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation—to bar the junta’s leader from participating in upcoming meetings and events. While international NGOs such as Amnesty International have also called for urgent accountability for the junta’s crimes, it is these local organisations that have led the call for sustained, strategic pressure—demanding not only justice but meaningful diplomatic consequences.

The 2021 coup escalated existing instability into a full-scale civil war that did not come to a halt for a mere natural disaster. Now, various ethnic armed groups and PDFs are engaged in guerrilla warfare against the military regime. As a result, Myanmar has witnessed high civilian casualties and the internal displacement of 3.5 million people.

Who Are the Rebels?

The resistance against Myanmar’s military junta is made up of a diverse and decentralised coalition of actors united by opposition to military rule. One of the most significant developments after the 2021 coup was the formation of the People’s Defence Forces—armed civilian groups operating under the broader political umbrella of the National Unity Government (NUG), which was formed in exile by ousted lawmakers and ethnic leaders. The PDFs emerged as a grassroots response to the brutal crackdown on peaceful protests and have become key players in the growing armed resistance.

Like many civil wars, Myanmar’s conflict is a confusing maze of acronyms and alliances. Alongside the PDFs, various ethnic armed organisations (EAOs)—some of which have fought the central government for decades—play a central role in the resistance. These include groups like the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), and the Chin National Front (CNF). While their historical goals differ, ranging from autonomy to full independence, many of these groups have entered strategic alliances with the NUG and other resistance actors to fight the common enemy: the military junta. Together, these forces have established parallel governance structures in parts of the country and gained control of significant territory, particularly in border regions and increasingly in central areas—many of which were also among the hardest hit by the recent earthquake.

When it comes to the future of democracy in Myanmar, the picture is more complicated. While the NUG formally promotes a democratic and federal vision for Myanmar and enjoys broad support among the pro-democracy movement, not all actors in the armed resistance share that long-term political vision. Some EAOs have historically focused on securing autonomy or protecting their ethnic communities rather than establishing a national democratic system. In this fragmented landscape, CSOs remain a vital and consistent force for democracy. Operating both within the country and in exile, CSOs have been at the forefront of documenting human rights abuses, advocating for political prisoners, organising grassroots support networks and calling for international accountability and solidarity. Unlike some military actors whose commitment to democracy may be tactical or limited, CSOs are among the clearest and most sustained voices pushing for a democratic, inclusive and civilian-led future in Myanmar.

Abusing a Disaster

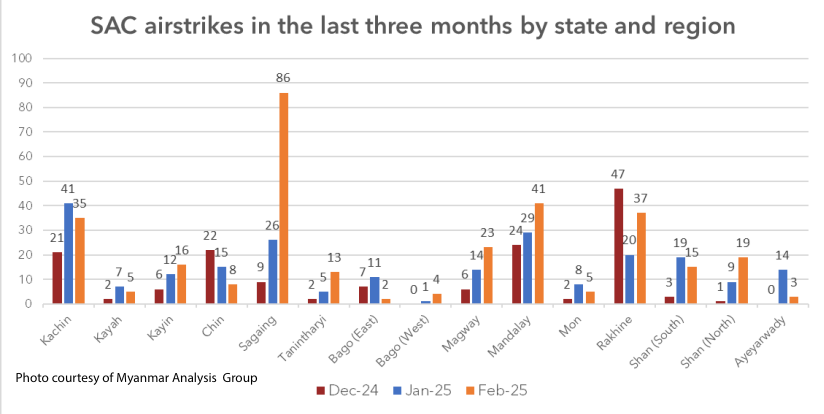

Military is the main tool of politics for the junta. The military blocks humanitarian aid and conducts indiscriminate airstrikes in earthquake-affected regions, many of which are dominated by rebel forces. At the time the natural disaster struck, the people of Myanmar were already enduring the effects of an ongoing civil war and human rights violations perpetrated by the military dictatorship. While the aftermath of the earthquake has its direct death toll, lingering effects from the widespread destruction of housing and infrastructure have caused immense challenges in providing shelter and medical assistance to those impacted by the devastation of the earthquake. According to a recent article, “Myanmar earthquake: Conflict sensitivity recommendations”, published on 1st April 2025, the collapse of sanitation systems and the severe lack of medical assistance are likely to lead to the outbreak of disease.

The junta is not only indifferent to this suffering—it is exploiting the destruction to gain a military advantage in the short term and authoritarian consolidation in the long run. Meanwhile, international developments in the international aid landscape have further compounded the crisis. According to The Economist, cuts to USAID under the Trump administration have severely reduced the resources available to hospitals on the Thai-Myanmar border, limiting the support they can provide to those in desperate need.

“The death toll is expected to rise considerably as more bodies are recovered from the collapsed buildings during rescue operations carried out amid searing 40°C heat.” - Myanmar Analysis Group, p. 2.

The devastating earthquake struck central Myanmar, with the epicentre situated near Mandalay—the country's second-largest city, home to 1.5 million people. There are unconfirmed reports suggesting that the majority of Mandalay’s buildings may have collapsed, with similar levels of devastation observed in surrounding towns and villages.

The disaster has already resulted in over 3000 confirmed deaths (at the time of writing), with thousands more injured or missing. The earthquake has overwhelmed the country’s already fragile infrastructure, making rescue and relief efforts even more difficult. Survivors are in urgent need of clean water, food, medical supplies and shelter. According to the UN, there is a critical shortage of essential items including first aid kits, blood transfusion equipment, pain medication and tents—leaving even basic first aid operations severely limited.

The full extent of the crisis is still unfolding. Communications infrastructure, which was already compromised by junta censorship, has now been further damaged—leaving many villages and towns unaccounted for.

"Support conflict-affected populations already struggling: Amid the ongoing conflict in Sagaing and Mandalay regions, many communities are already struggling in terms of displacement, day-to-day safety, livelihoods, and access to basic services." - Myanmar Analysis Group, p. 4.

"[SAC] has a history of preventing aid from reaching areas where it perceives the assistance will reach its opponents. Many people fear that the SAC will use the earthquake as an entry point for regaining territory, for example, by moving troops in with the aid." - Myanmar Analysis Group, p. 3.

Since the SAC does not control many of the earthquake-affected areas, it uses some humanitarian phrasing to move its military units to the areas “to provide assistance”, but also, because such areas cannot defend themselves at the moment.

International Response and Aid Efforts

The global community has voiced concern over the junta’s handling of both the political crisis and the recent natural disaster. Countries such as the United States have pledged meagre financial assistance, while some countries including the neighbouring states—India, China, and Thailand—have sent rescue teams and emergency aid.

However, the effectiveness of international relief efforts is being severely limited by the military’s stranglehold on aid distribution and by the conflict itself, which renders many areas inaccessible.

Prospects for Myanmar’s Future

The current moment in Myanmar carries a trifold significance for the near future. Firstly, the military will use the aftermath of the disaster as an opportunity to intensify its assaults on rebel strongholds. Secondly, the catastrophe could fuel greater resistance among civilians, further legitimizing the NUG coalition - but greater willingness to resist will not be effective if vital resources run out and infrastructure has been destroyed. Lastly, all this could amplify international scrutiny of the regime - however, on this, it must be noted, that the international community has not been able to stop the atrocities in the past either.

While Myanmar has long been marked by ethnic and religious divisions—such as those between Buddhist nationalists and Rohingya Muslims—the present moment has seen a rare convergence of shared suffering and solidarity. In many of the earthquake-affected areas, particularly in central Myanmar, cultural values rooted in reciprocity, trust and a deep sense of communal sharing have fostered mutual support across diverse communities. Buddhist monasteries, pagodas and mosques alike have been reduced to rubble, underscoring how the disaster has impacted all groups. However, this fragile unity is not guaranteed to last. As resources grow scarcer and state obstruction continues, there remains a risk that these social bonds could fray—reminding us of the urgent need for equitable and conflict-sensitive relief efforts.

The combination of civil war and natural disaster has prompted questions about the junta’s ability to retain power. The earthquake has laid bare the already evident weaknesses of the regime. Far from being a potential turning point, the military’s mismanagement of the crisis has only deepened public mistrust and further destabilised what little internal coherence remained. The junta's inability to respond effectively—not just to the humanitarian emergency but also to the collective will of the people—reinforces how fractured and fragile its grip on power truly is. While the junta intends to use this moment to increase its power, the earthquake also means its own resources have been limited by this crisis. How this will alter the trajectory of the civil war remains to be seen.

Today, the summary is that Myanmar has simply faced too much. It faces the “polycrisis” of civil war and natural disaster. The actions of the junta require condemnation, but furthermore, the immense suffering of the civilian population requires a humanitarian response immediately, and in the long term, return even to the narrow path toward democracy that existed before the coup.

Furthermore, it is essential that narratives surrounding Myanmar do not reduce its people to passive victims or mere recipients of international aid. Despite facing extraordinary repression and disaster, countless individuals and communities across the country continue to act with courage and agency—organising mutual aid and resisting authoritarianism on the ground. They are acting not just because they believe it to be right, but because they know they have to act to survive against the regime. From local rescue efforts to underground networks of civil resistance, the people of Myanmar are not only enduring multiple crises—they are shaping the fight for a federal nation and a democratic future. Any response, whether humanitarian or political, must recognise and support this agency rather than speak on their behalf.

Sources:

Myanmar Analysis Group, “Myanmar earthquake: Conflict sensitivity recommendations”, 1 April 2025.

Jonathan Head & Lulu Luo, “A turning point in Myanmar as army suffers big losses”, BBC, 9 November 2023. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-67305690 (accessed 4 April 2025).

Rebecca Henschke, “Myanmar junta continues air strikes after devastating earthquake”, BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy7x7r8m3xlo.amp (accessed 4 April 2025).

YLE, “Järistys iski Myanmarissa jo valmiiksi hauraaseen yhteiskuntaan – 'Vain diktatuuri estää avun pääsyn perille’”, 1 April 2025. Available at: https://yle.fi/a/74-20152456 (accessed 4 April 2025).

Melissa Crouch, “Myanmar’s Military Coup d’État is Unconstitutional”, Verfassungsblog, 2 February 2021. Available at: https://verfassungsblog.de/myanmars-military-coup-detat-is-unconstitutional/ (accessed 4 April 2025).

Kate Lamb & Rebecca Ratcliffe, “Myanmar junta accused of blocking aid for earthquake victims as airstrikes continue”, The Guardian, 1 April 2025. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/apr/01/myanmar-earthquake-junta-accused-blocking-aid (accessed 4 April 2025).

UN News, “UN human rights chief points to ‘textbook example of ethnic cleansing’ in Myanmar”, 11 September 2017. Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/09/564622-un-human-rights-chief-points-textbook-example-ethnic-cleansing-myanmar (accessed 4 April 2025).

Sue-Lin Wong, “Why is it so hard to get aid to Myanmar?”, The Economist. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HG67qaIy0fw (accessed 3 April 2025).

Freedom House, “Myanmar: Election brings country closer to democracy”. Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/article/myanmar-election-brings-country-closer-democracy (accessed 3 April 2025).

Progressive Voice Myanmar, “Open letter from 319 organizations to disinvite Min Aung Hlaing and exclude Myanmar military junta from BIMSTEC”, 29 March 2025. Available at: https://progressivevoicemyanmar.org/2025/03/29/64578/ (accessed 3 April 2025).

Reuters, “Who is giving aid to Myanmar after the earthquake?”, 1 April 2025. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/doctors-dogs-dollars-who-is-giving-aid-myanmar-after-earthquake-2025-03-31/ (accessed 4 April 2025).

Thin Lei Win, “Myanmar in ‘polycrisis’ as US aid freeze compounds long-term donor neglect”, The New Humanitarian. Available at: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2025/02/18/myanmar-polycrisis-us-aid-freeze-compounds-long-term-donor-neglect (accessed 3 April 2025).

Dustin Barter, “Myanmar: A microcosm of aid cuts and humanitarian choices”, ODI Global. Available at: https://odi.org/en/insights/myanmar-microcosm-aid-cuts-humanitarian-choices/ (accessed 3 April 2025).

Myanmar Election Watch, “History of Elections in Myanmar”. Available at: https://myanmarelectionwatch.org/en/history-of-elections-in-myanmar (accessed 3 April 2025).

Contributors:

HS

Veli-Valtteri Lehtonen (Student Network on Future Democracy)

Carlynne Meissenheimer (Democracy International e.V)